Tracing the Beatles' Irish

Ancestry in Liverpool

Clarence

Dock area

Liverpool,

L3

"Through these dock gates passed most of the

1,300,000 Irish migrants who fled the Great Famine and

“took the ship” to

Liverpool in the years 1845-52.

Remember the Great Famine"

People

have always travelled between Ireland and England and records show that there

were families with Irish surnames in Liverpool as early as 1378. However, it

was when Liverpool gained prominence as a port city in the mid-18th century

that it became the primary entry point for Irish migrants as they made their

way to England.

The

Irish population in England grew through the 19th century when many poor

labourers, drovers and artisans emigrated due to economic reasons. However,

poverty was not always the motive. Middle class Irish also arrived and some

made their mark on the history of Liverpool. One, Michael Whitty, founded the

Liverpool Fire Brigade and the Liverpool Daily Post newspaper. Another

prominent figure, William Brown, financed the building of the public library

(which we will read about elsewhere) and ultimately had a street named in his

honour.

In

1841, 20% of the Irish living in England and Wales were found in the Liverpool

area. Due to tragic events this figure would increase enormously over the next

ten years.

In the 'Pool they told us the story

How the English divided the land.....

An

Drochshaol (the Great Hunger) is the name given to the famine in Ireland

between 1845 and 1852.

An

estimated two-thirds of the predominantly Roman Catholic Irish population

toiled on tenant farms upon which they had to pay rent to their rich, and

largely absent, English landlords. Potato was the staple (and often only) food

of the labouring classes as it was the only crop that could be grown in

sufficient quantities to feed them, especially in winter.

In 1845

the weather appeared to have been favourable and the Irish farming community

had good reason to expect a bumper harvest. However, on digging up the potatoes

the farmers were met with a black gooey mess. As much as 50% of the potato crop

was lost and as the rural community only grew what they needed for that year,

with little put aside in case of trouble, they were faced with starvation.

A starving

Irish family from Carraroe, County Galway, during the famine. (National Library

of Ireland)

The

problem only got worse. The crop of 1846 was all but a total failure and there

was a further poor harvest in 1847. The effect of three disastrous years in

succession was devastating. No precise figures seem to be available but it is

generally agreed that between 500,000 and more than one million people lost

their lives through hunger or disease.

Some would argue the figure as high as 5.16 million, two thirds of the

entire population at that time.

How

could so many people be allowed to starve to death in the heart of the world’s

wealthiest empire?

Although

Ireland's production of corn, wheat, barley and beef was unaffected during the

famine her English landlords made a bigger profit exporting these food products

and shamefully sold them elsewhere. During this period, around £1 m of corn and

barley were exported from Ireland to mainland Britain, along with quantities of

dairy produce. Driven on by free trade, foodstuffs left Ireland - despite the

fact that it was desperately needed in Ireland itself. Around 70% of Politicians were landowners

themselves or the sons of landowners, and they were slow to react. Although the

government started exporting food from India and elsewhere in the Empire to

Ireland the distribution was not maintained properly so food did not reach the

poor. In 1847 the government set up soup kitchens where the labouring

communities could eat for free. Up to three million were fed under this scheme

but it was discontinued after only 6 months.

Eviction

A lack

of action from the majority of landlords in Ireland made matters worse. Showing

no sympathy for those who worked on their land they evicted anyone who could

not pay their rent, the landlords needing little excuse to rid their estates of

impoverished farmers and labourers.

In the

years between 1846 and 1854 perhaps as many as 500,000 people were evicted from

their homes and farms.

With no

food and no home, many decided to leave Ireland and try to make a new start

elsewhere. With dreams of a better life in the United States or Canada, the

Irish made their way to the nearest port where they could seek passage to the

New World: Liverpool.

A thousand years of torture and hunger

Drove the people away from their land

A land full of beauty and wonder

Was raped by the British brigands!

Goddamn! Goddamn!

Irish

Emigrants Entering Liverpool (David Jacques)

The

famine led to the biggest mass migration of the 19th century. About 1.5 million

poverty stricken men, women and children left Ireland for the US, another

340,000 for Canada, 300,000 for the British mainland and 70,000 for Australia.

Many of

the desperate thousands crossed the Irish Sea on barely seaworthy vessels which

soon came to be known as 'coffin ships'. One ship leaving Westport in County

Mayo sank, drowning its passengers within sight of the horrified onlookers who

had only just bid them farewell. Some families had been given the small amount

for the crossing by their landowners' agents, who seized the opportunity to

clear them off the land once and for all. Others were carried as live ship's

ballast asking only to be fed and given safe passage to Liverpool and beyond.

Below

Deck

(Rodney Charman)

Very

often these overloaded ships reached Liverpool after losing a third of their

passengers to disease, hunger and other causes. Many who could not afford the

passage abroad simply took the boat to Liverpool or Glasgow, viewing these

temporary stops as stepping stones in their dreams of making it abroad in the

near future. The harsh reality was that in 1846, 280,000 people entered

Liverpool from Ireland but only 106,000 moved on. During the first main wave of

famine emigration from January to June 1847, about 300,000 sick and poor Irish

refugees sailed into the city, but only 130,000 emigrated.

As the Clarence

Dock plaque states, it is thought that approximately 1.3 million migrants*

passed through the port in Liverpool. By the time the famine ended, around

1852, there were some 90,000 Irish born who were living in Liverpool, a figure

which had swollen the population by 25%.

Given

the circumstances of their migration, the vast majority of the Irish who

arrived in Liverpool were starving, poor and extremely vulnerable. Some quickly

moved onwards and out into the city but those who stayed near the docks were at

great risk and were often preyed upon. Gangs of unscrupulous characters sprang

up almost immediately and found an easy livelihood taking the little money the

Irish possessed upon arriving on the Mersey docks.

Liverpool

must have seemed hostile and unwelcoming. Those Irish who arrived were quickly

branded as "paupers, vagrants and thieves" with certain media outlets

projecting an intense anti-Irish feeling to prevent any solidarity there may

have been with the Irish from the English working class. Vicious Orange Lodge

attacks were common on the vulnerable, murders and suicides were near daily

occurrences as were the corpses that were fished out of the Mersey. As some

historians have convincingly argued, the suggestion that these people chose to

stay on in Liverpool rather than continue their journey is laughable.

In the

"Condition of the Working Class in England" (1845) the social

scientist and political theorist Friedrich Engels had this to say on the

subject of Irish migration:

"These Irishmen who migrate for

fourpence to England, on the deck of a steamship on which they are often packed

like cattle, insinuate themselves everywhere. The worst dwellings are good

enough for them; their clothing causes them little trouble, so long as it holds

together by a single thread; shoes they know not; their food consists of

potatoes and potatoes only; whatever they earn beyond these needs they spend

upon drink. What does such a race want with high wages? The worst quarters of

all the large towns are inhabited by Irishmen. Whenever a district is

distinguished for especial filth and especial ruinousness, the explorer may

safely count upon meeting chiefly those Celtic faces which one recognises at

the first glance as different from the Saxon physiognomy of the native, and the

singing, aspirate brogue which the true Irishman never loses. The majority of

the families who live in cellars are almost everywhere of Irish origin. In

short, the Irish have, as Dr. Kay says, discovered the minimum of the necessities

of life, and are now making the English workers acquainted with it. Filth and

drunkenness, too, they have brought with them. The lack of cleanliness, which

is not so injurious in the country, where population is scattered, and which is

the Irishman's second nature, becomes terrifying and gravely dangerous through

its concentration here in the great cities. The Milesian deposits all garbage

and filth before his house door here, as he was accustomed to do at home, and

so accumulates the pools and dirt-heaps which disfigure the working- people's

quarters and poison the air. He builds a pig-sty against the house wall as he

did at home, and if he is prevented from doing this, he lets the pig sleep in

the room with himself. This new and unnatural method of cattle-raising in

cities is wholly of Irish origin. The Irishman loves his pig as the Arab his

horse, with the difference that he sells it when it is fat enough to kill.

Otherwise, he eats and sleeps with it, his children play with it, ride upon it,

roll in the dirt with it, as any one may see a thousand times repeated in all

the great towns of England.

The filth and comfortlessness that prevail in

the houses themselves it is impossible to describe. The Irishman is

unaccustomed to the presence of furniture; a heap of straw, a few rags, utterly

beyond use as clothing, suffice for his nightly couch. A piece of wood, a

broken chair, an old chest for a table, more he needs not; a tea-kettle, a few

pots and dishes, equip his kitchen, which is also his sleeping and living room.

When he is in want of fuel, everything combustible within his reach, chairs,

door-posts, mouldings, flooring, finds its way up the chimney. Moreover, why

should he need much room? At home in his mud-cabin there was only one room for

all domestic purposes; more than one room his family does not need in England.

So the custom of crowding many persons into a single room, now so universal,

has been chiefly implanted by the Irish immigration.

And since the poor devil must have one

enjoyment, and society has shut him out of all others, he betakes himself to

the drinking of spirits. Drink is the only thing which makes the Irishman's

life worth having, drink and his cheery care-free temperament; so he revels in

drink to the point of the most bestial drunkenness. The southern facile

character of the Irishman, his crudity, which places him but little above the

savage, his contempt for all humane enjoyments, in which his very crudeness

makes him incapable of sharing, his filth and poverty, all favour drunkenness.

The temptation is great, he cannot resist it, and so when he has money he gets

rid of it down his throat. What else should he do? How can society blame him

when it places him in a position in which he almost of necessity becomes a

drunkard; when it leaves him to himself, to his savagery?"

I had

to read that a few times to know which side he was on.

"It is they [the Irish] who inhabit the

filthiest and worst of these unventilated courts and cellars." Dr Duncan of Liverpool, speaking in 1842.

William

Henry Duncan, was born on 27 January 1805 at 108 Seel Street, a house which,

155 years later, would become Allan William's Blue Angel club. After qualifying

as a Doctor of Medicine in Edinburgh in 1829 he returned to Liverpool to work

as a General Practitioner in the poorest quarters of the town. He was rapidly

overwhelmed with cases and quickly realised that it was no co-incidence that

the majority of his patients were those living in slum conditions. Until

something significant was done to change this squalor his efforts would be

negligible.

Duncan's

great achievement was to draw the authorities attention not only to the plight

of the thousands of slum dwellers, but also the epidemics which were bound to

arise and seep into the wealthier districts of the city. His efforts and those

of other like-minded philanthropists in the city led to action in Parliament

resulting in Duncan's appointment as the first Medical Officer of Health on 1

January 1847.

It was

a role which would occupy him for the rest of his life. The number of Irish who

had arrived in Liverpool and not subsequently moved on was conservatively

estimated to be around 80,000 and more were continuing to arrive every day.

As much

a problem today as it was then, a huge influx of additional mouths to feed can

cripple a city and in 1847 Liverpool the authorities could simply not cope.

That June, under the newly passed Poor Law Removal Act, around 15,000 migrants

were deported back to an uncertain fate in Ireland.

It was

calculated that 35,000 people, mainly Irish, were inhabiting court dwellings or

cellars, with some 5341 of the latter described as 'wells of stagnant water',

without light or ventilation. With so many starving people mainly left to fend

for themselves, countless thousands died, 40 or 50 deep, in appalling

conditions.

The

Courts were accessed by a narrow gate or passageway that, from the outside at

least, might have looked like a normal doorway or entry in the front of a

terrace of houses. However, these would lead directly into the court-yard, a

central square, about 20-30 feet long by about 10-15 feet wide, around which

blocks of rooms had been built, often up to 4 floors high. Each tenement block

accommodated dozens of families. At times, there could be more than one family

living in each room.

These

confined urban communities would not have had any form of localised water

supply, and in most cases the only sanitary provision for the hundreds of

people living around each court was a single, communal water-closet placed at

one end of the yard (see centre rear of the above photo).

The

water-closet would generally consist of a wooden bench with a lavatory hole cut

in it, suspended over an earthen pit, the contents emptied irregularly by the

"Night Soil" men. Worse were those courts with earthen middens, not

water closets as there were few street sewers at the time. With some of these

privies situated directly under windows once can only imagine the stench and

pestiferous gases from their foul contents flowing in to the houses whenever

these were opened. In 1841 it was estimated that as many as 50% of the

population lived in courts with the districts of St. Paul, Exchange and

Vauxhall having the highest percentage of this type of dwelling.

Dr

Duncan had quickly identified that these overcrowded living quarters were

breeding grounds for disease, and despite numerous attempts to improve sanitary

conditions, the “Irish Fever” persisted. Typhus, dysentery and cholera swept

through the population. It is estimated that in Liverpool as a whole, 60,000

caught the fever and 40,000 contracted dysentery. In 1847, 5,845 people died

from typhus in just a few weeks. The epidemic was so severe that floating

hospitals and fever sheds were built along the Mersey.

If you had the luck of the Irish

You'd be sorry and wish you were dead

You should have the luck of the Irish

And you'd wish you was English instead!

Life with the O'Leannains

Stepping

off one of the Irish boats and into this living hell was James Lennon, the

great grandfather of Beatle John.

James,

son of Patrick Lennon, was born in County Down, Ireland in 1829. Their surname

was Irish, derived from O'Leannain or O'Lonain.

There

is no evidence that Patrick ever left Ireland. However, at the height of the

famine and with no forseeable future, James made the crossing, perhaps with his

father's encouragement, and entered Liverpool through the huge gates of

Clarence Dock alongside thousands of his countrymen.

Despite

the end of the Famine around 1849-1850, and subsequent decrease in the number

of migrants entering Liverpool most of the Irish already here remained and

carried on integrating with the local life. They were ready to accept any job,

especially in the newly expanding seaport, working as dockers and seamen. Many

Irish workers were forced to take low-paid, labour-intense jobs at the docks,

processing plants, in the chemical industries, and as warehouse and

construction workers. Those that stayed gravitated toward established Irish

communities. The Irish Catholic community developed predominantly around the

Scotland Road area with St. Anthony’s Church at the slum ridden heart. Further

Catholic churches quickly sprung up throughout the 19th century.

James

Lennon was one who stayed, working locally as a warehouseman and cooper (barrel

maker) and living in the cramped squalor of Vauxhall Road, a mile north of the

city centre, just behind the docks.

It was

probably whilst living in Vauxhall that James met Jane McConville for the first

time. Her parents James and Bridget McConville had moved to Liverpool with Jane

and her two brothers John and Richard between 1840 and 1849. Like James Lennon

the McConville's came from County Down and had probably fled similar hardships.

On 29th

April 1849 an earlier Len-Mac partnership was formed when James Lennon, aged 20

married Jane McConville, aged about 18 (b.1831) at St Anthony's (above).

Like the majority of the Irish arriving in

Liverpool Jane was illiterate, signing her name with an "X". The

marriage certificate gave their addresses as Vauxhall Road and Saltney Street

and their respective fathers were Patrick Lennon, a farmer and James McConville,

an engineer.

Following

the marriage James moved into court housing with his new in-laws on Saltney

Street, spitting distance from Clarence Dock where he had first arrived in

Liverpool.

A court in Saltney Street, 20 December 1906 (L.R.O.)

Saltney Street,

Liverpool 3

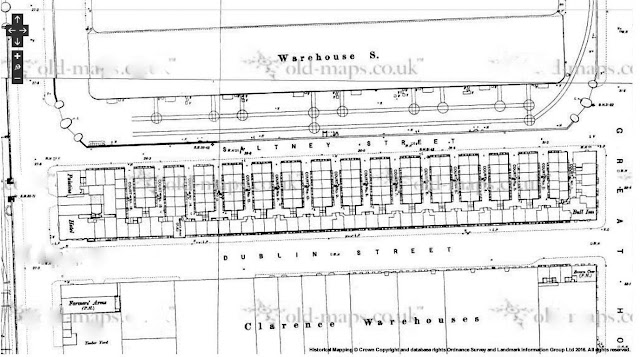

An 1891

map of Saltney Street (click to enlarge). The Palatine pub facing Clarence Dock

backed onto Court No.16. James Lennon was living at No. 12 Court in 1851.

According

to the 1851 census, James Lennon and his wife Jane were living in No. 12 Court,

Princes Place at 51 Saltney Street with their daughter Elizabeth who had been

born in 1850 and 11 other people. Four of these were probably Jane's family -

her parents James McConville (b.1810 Ireland) and Bridget McConville (b.1811

Ireland) and her brothers John McConville (b.1834 Ireland) and Richard

McConville (b.1840 Ireland).

The

1908 Ordnance Survey map (above) shows a street of very small block houses,

little alleys or courts containing ten houses each. The courts were named after

the adjacent docks - Clarence Place, Trafalgar Place, Victoria Place, Waterloo

Place and Princes Place where the Lennon’s lived. Maps show nine public houses in the immediate

vicinity - one on every street corner and more halfway along. Inevitably few

men could pass them on their way home without going in for a quick one,

spending what few pennies they had earned on ale or spirits, despite their

families starving and shivering a few yards away.

The Great

Howard Street end of Saltney Street (1912). This end block has a public house on each corner, The Bull

on the left and the Stanley Arms on the corner with Saltney Street seen on the

right. The terraced houses fronting court properties are still standing to the

immediate right of the pub but it was about this time that the courts were

being cleared from the street. The section of the street further down the

towards the dock road (seen here on the extreme right of the photograph above)

had already been replaced by the taller landing houses seen in the 1920 and

1966 photographs below. Today only The Bull public house remains (below)

The dock end of Saltney

Street looking towards Great Howard Street on 8 March 1920 (above) and 25

November 2012 (below). Note the men gathered outside the Palatine Hotel on the

bottom right of the above photo watching the photographer whom I am assuming

was stood on the dock wall**.

The author David Lewis writes that Saltney Street was hard by the docks of this great global seaport, ocean liners steaming up and down the River Mersey right at the end of the street. It's still there today though the horrors of its cholera-infested housing have long since disappeared. Today the other side of the street is still taken up by the long flat wall of Stanley Dock’s warehouses and any houses were squeezed into the industrial fabric of the area.

Children

in Queens Place Court, Saltney Street 1909

David

Lewis vividly describes how life would have been when he imagines barefoot children running along greasy

cobbles, giant horses hauling wagons of barrels, the air full of smoke and

metallic shrieks. Over the huge dock wall is a forest of masts and rigging, the

occasional funnel and blasts of smoke from steamships and Irish boats.

Wonderful,

evocative stuff.

Many of

the Irish migrants arrived in Liverpool with little more than the clothes on

their backs. They were the poorest of the poor and yet they had pay

unscrupulous private landlords between 2s 6d and 6s a week for the privilege of

living in such atrocious squalor. In many cases several or more families were

forced to cohabit a single room in order to share the rent. Those with no means

to pay were moved on countless times, the Lennons amongst them, census records

and other documents showing they were always on the move, at least eight of

their babies being born at different addresses. We'll find out where they went

in a future post.

.jpg)

An

early 1900s photo of a typical squalid room in Saltney Street (LRO)

Saltney

Street, circa 1966 showing the landing houses present on the 1920 photograph.

These started to replace the original court dwellings around 1911 but today

these too have disappeared.

Saltney

Street today looking towards Clarence Dock (left) and Great Howard Street

(right). The tarmac has worn away in parts revealing the original cobbles,

relics from the Lennon's and McConville's time there.

Clarence

Graving Dock where the Irish arrived in Liverpool.

Notes:

* I use

the word migrants because Ireland is part of the United Kingdom. These were

people moving within their own country.

** The

photographer could just as easily have been standing on the platform of

Clarence Dock station, part of the Liverpool Overhead Railway. Adjacent to the

dock of the same name it was opened on 6 March 1893 by the Marquis of Salisbury

no less.

Sources:

Books:

The

Beatles Liverpool Landscapes (David Lewis)

Web:

http://www.historylearningsite.co.uk/ireland_great_famine_of_1845.htm

http://www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/famine/coffin.htm

http://www.irishholocaust.org/liverpoolandthegreat

Liverpool

Echo

http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/liverpool-life/liverpool-lifestyle/2011/03/15/trace-your-family-s-irish-heritage-as-part-of-the-echo-s-irish-week-100252-28335653/#ixzz2LcGkKBrV

http://www.merseyreporter.com/history/historic/irish-immigration.shtmlhttp://www.yoliverpool.com/forum/showthread.php?2518-Irish-Famine/page2

http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/victorians/famine_01.shtmlhttp://www.exodus2013.co.uk/irish-migration-into-liverpool-in-the-19th-century/e

here: http://www.charlotteobserver.com/living/travel/article9100922.html#storylink=cpy

http://www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/mol/visit/documents/Liverpool-Irish-community-trail.pdf

You can

see more of Rodney Charman's beautiful paintings of the Irish Famine ships

here: http://www.marine-artist.com/irish-famine-ships/

For the

accuracy of John Lennon's family tree we have Michael Byron to thank. You can

read it in full here: http://brakn.com/Jack1.html

Lyrics

from "The Luck of The Irish"

by John Lennon and Yoko Ono (from the 1972 album Some Time In New York City)

Great where can I get a paper back copy ?

ReplyDelete