It may well be that after all these years journalists have finally learned how to ask Paul McCartney interesting questions. After the excellent interviews in Esquire (2015) and GQ (2018) the current September edition of that latter publication has another superb piece, ostensibly to promote the reissued super-deluxe edition of 'Flaming Pie', though it barely gets a passing mention. Instead, a relaxed Paul seems happy to talk about a vast range of subjects (anything you like)*

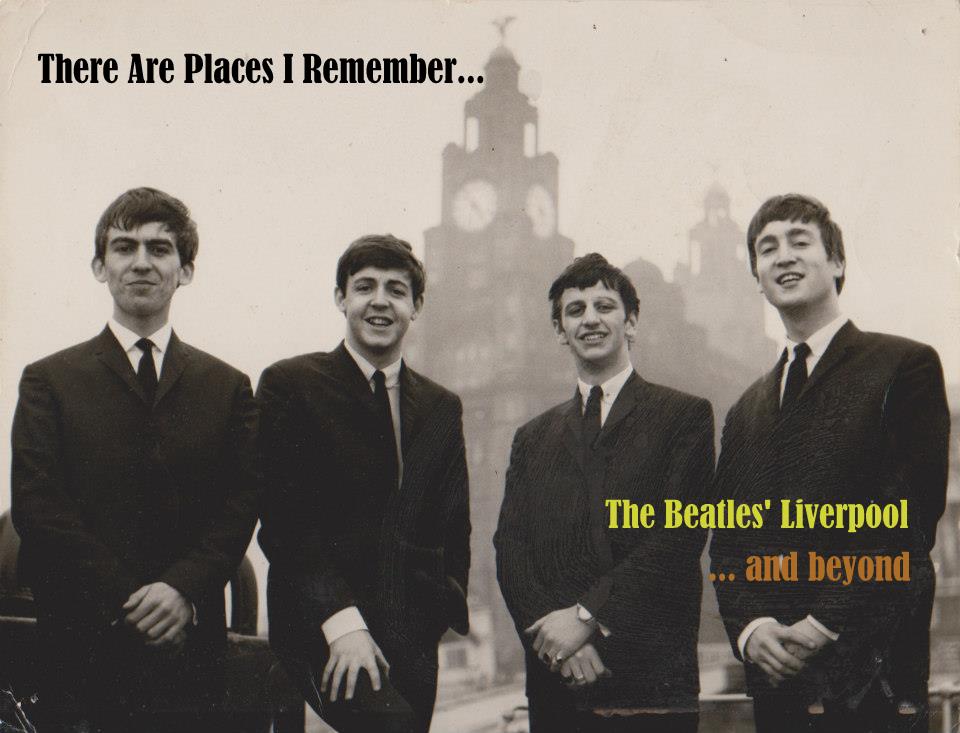

As always, the most interesting bits for me are when he discusses those 'early days' 'in Liverpool', to name just two McCartney songs or, as I call them the 'Tune In' days, to name just one Mark Lewisohn book.

While his memories of Beatlemania can sometimes appear a bit blurry around the edges, unsurprising when you consider how much they did in such a relatively short period, and the anecdotes can sound tired through the constant retelling+, when he's asked about the more carefree, pre-fame days a light switch seems to flick on and he's right back there.

I've said this before, somebody really needs to sit down with him and get all of the pre-fame stuff written down instead of asking him about the Beatles again. Likewise Ringo who has said in interviews that he's occasionally asked to do an autobiography but refuses because the publishers really only want to know about those seven years. He's said the really interesting stuff is the pre-fab days. I agree. There's so much fascinating material in 'Tune In' about Ringo's life up to the end of 1962 that it would almost make a stand-alone book. He's 80 years old now. I for one would love to read about the first 20 years of Ringo's life growing up in the Dingle. That said those years doing Thomas The Tank Engine were pretty special so I can understand the interest from publishers.

In my fantasy world I would drive Paul or Ringo around Liverpool stopping at various locations and get them to go into great detail about their memories of the place because sadly when they're gone they're gone. Of course, Paul is not averse to doing this to an extent, albeit on his own terms. He's often mentioned how he gives his passengers a guided tour whenever he's driving in the city. In fact he mentions it below in the new interview. It's a pipe dream I know and I suppose the closest we'll ever get to it is by watching "Carpool Karaoke" but for a moment just imagine driving him to Garston bottle works for example and saying "right, tell me about the night Allan Williams brought you all here to try and persuade Tommy Moore to rejoin the group." He's probably never been asked about that in 60 years.

Anyway a great interview (accompanied by some nice photos by Mary McCartney). Here's the bits about Liverpool which will be of interest to readers of this blog.

By Dylan Jones, 4 August 2020

What’s

the first thing you do when you go back to Liverpool?

Most

of the time I fly up. So I’ll get to Liverpool airport, the John Lennon

Airport, and I’ll have a car [waiting for me] and I’ll drive myself from

thereon. I’m normally with someone, one of my mates... One time was with Bono,

actually, and we drove together because we were both going to the same event at

Liverpool Arena.

I

like driving and I don’t want to be driven around Liverpool. And I know all the

routes, you know? Most of the time I’m driving to LIPA [Liverpool Institute For

Performing Arts, co-founded by McCartney in 1996] and on my way I pass all the

old haunts and it’s like a guided tour, with me as the tour guide. I’ll say,

“And this is where John’s mother, Julia, lived and we used to go round and

visit her. And this is the street here where I had my first girlfriend.”

So

it’s all that. “This is where I did this; this is where I took this girl

out...” I can remember lots of stuff. “This is where we did our first little

gig, at a place called The Wilson Hall, and then over here me and John used to

walk down this street with our guitars and then I would walk up there, to his

house, across the golf course.”

This is very interesting. Paul recalls his first little gig with the Quarry Men as being at the Wilson Hall. This ties in with Colin Hanton's memory that their first paid booking was Wilson Hall for Charlie McBain. It's been suggested elsewhere that Paul's first appearance was at the New Clubmoor Hall in Norris Green.

When Paul's thinking about Wilson Hall he's clearly just come out of Liverpool John Lennon Airport, driven past the old airport and the Matchworks on his left and is heading for Aigburth Road which will take him straight through to town. As he comes over the railway bridge he can see Woolton Carpets on his right, the site of Wilson Hall in the late 1950s.

So

I give the guided tour until I get into the city centre and I say, “This is a

little place where we used to play in the basement, a little illegal club run

by this Liverpool black guy called Lord Woodbine. That’s when it was just me,

John and George. I was drumming as we didn’t have a drummer at the time.” Just

millions and millions of memories all come flooding back.

When I went back to

Liverpool with James Corden for the “Carpool

Karaoke” special, he was very good, because he just kept me going, asking me

questions, plus he’s someone who it’s cool to hang out with, you know? He’s

entertained as well as entertaining.

I did the same thing: “This is the church

where I used to sing in the choir, this is Penny Lane and this is the

barber.” Every time I go up there, it’s the same. The only difference with the

thing I did with James is that I’d never been inside my old house. I hadn’t been

back since I left it. James suggested doing it. I was always a little

apprehensive about going back. I didn’t know if it was going to be nice or

whether I would get bad memories or whatever, although I don’t really know what

I was worried about. But it was fabulous – really great. I was happy to be able

to tell him all the stories, of my dad, my brother and our time there. It

brought back a lot of nice memories actually, so I loved it.

How

much Scouse slang do you still use?

A

little bit here and there. When you’re not actually living there, you don’t

come up with much, but I still use a bit. If something’s a bit old you might

say it’s kind of “antwacky” or somebody’s going “doolally”. They’re good words,

so they occasionally creep into your conversation, but obviously not as much as

when I lived there. Someone reminded me not so long ago that I’ve actually

lived longer down south than I had in Liverpool, as I only lived there for 20

years. But I love it. I love Liverpool. I love the history of it. I love my old

school, which is now LIPA, and I go there a couple of times a year and take

songwriting classes and for the graduation, which was cancelled this year

unfortunately.

Paul (centre) at the LIPA graduation, 26 July 2019. Every year he personally presents every graduate with a scroll and poses with them for an individual photograph.

Tell

me about your school. You loved it, didn’t you?

The

memory of the school, I always think, is very important, because I say to

people, “Half The Beatles went there!” Me and George went to that school and

John went to the art school next door, which is now part of LIPA so three

quarters of The Beatles, in one way or another, are connected to LIPA. That

always hits me. Whenever I do a speech at the graduation, I always remember my

mum and dad coming to events at the school when we were kids, like speech day,

and your mum and dad would be there all proud of you and stuff, so when I’m

standing there, talking to all the parents and all the kids, I get quite

emotional. I’ve got a million memories in that place and most of them are

great, most of them are lovely.

I was very lucky. I had a great family. I don’t

remember anyone ever getting divorced or anyone being weird. There were a few

drunks, but outside of that, it seems to be a very loving family. So I have a

lot of very affectionate memories of that time and of those people.

Liverpool

FC supporters often sing “All You Need Is Klopp”. Do you have any other

favourite terrace appropriations of Beatles songs?

I’m

not sure, really. There’s a great old piece of film from the 1960s of the

Liverpool fans singing “She Loves You”, with the Kop all singing, “Ooooooh!”

All the kids, everyone, it’s quite moving. The camera goes in on the crowd and

there are all these young Beatles, all these kids with the hairstyle, and

they’re all singing “She Loves You”. They know all the words. That piece of

film was always a high spot for me. [Check it out on YouTube, as it’s

magnificent.] I know a lot of crowds do “Hey Jude” and when we go on tour,

especially in South America, the crowds are like football crowds anyway – “Olé,

olé, olé, olé!” You get a lot of that. What we do is we quickly figure out

what key it’s in and then we back the audience. We become their backing band.

18 May 1968: Paul and Ivan Vaughan arrive at Wembley to watch Everton play West Bromwich Albion in the F.A. Cup Final.

As

a proud Evertonian, would you have been fine with the Premier League cancelling

this season so Liverpool couldn’t be named champions?

Years

ago I decided I was going to support Liverpool as well as Everton, even though

Everton is the family team. A couple of my grandkids are Liverpool fans, so we

are happy to see them win this year’s Premier League. When people ask me how I

can support them both I say I love both and I have special dispensation from

the Pope.

Unfortunately, and this is coming from me, a devout red, we all know that if you're born a blue you're forever a blue. Paul just doesn't want to offend (at least) 50% of the city.

Two months on from Everton at Wembley here's Paul with a Liverpool FC rosette, 28 July 1968 (Don McCullin)

Do

you ever reflect on the uniqueness of your position?

Do

I ever! Like, always. Just give me a drink and sit me down and ask me

questions. I tell you, I’m sitting there and I’m thinking, “My God, what about

that?” The Beatles. I mean, come on, there are so many things. Obviously a lot

of other people say things [too]. I remember Keith Richards saying to me, “You

had four singers. We only had one!” Little things like that will set me off and

I think, “Wow.” That is pretty uncanny. And writers. Not just singers, but

writers. So you had me and John as writers and then George was a hell of a

writer and then Ringo comes up with “Octopus’s Garden” and a couple of

others... I love to go on about it, because in going on about it, it brings

back memories. I do think it’s uncanny.

You know, number one: how did those

four guys meet? OK, well I had a best friend, Ivan, who knew John, so that’s

how I met John. I used to go on the bus route to school and this little guy got

on at the next stop and that was George. So that was kind of quite random. And

then Ringo was some guy from the Dingle and we met him in Hamburg and just

thought he was a great drummer.

But

the idea that all these quite random people in Liverpool should come together

and actually be able to make it work? I mean... the thing is, we were pretty

bad at the beginning. I mean we [The Beatles] weren’t that good. But with all

the time we had in Hamburg, we just got good [through practising]. We became

good. If somebody said, you know, “I’m gonna tell Aunt Mary ’bout Uncle John,”

we didn’t all look at each other wondering what key it was in. It was, “Bam!”

Everyone knew. “Bang! It’s ‘Long Tall Sally’. Here we go.”

We

had a lot in common and that’s just the musical aspect. Then you go into all

the other aspects. One thing about The Beatles is that we were kind of like an

art band. John went to art college, so with him and Stuart [Sutcliffe] there

was that connection. I was very into art anyway and it wasn’t just art, it was,

like, culture, with a small “c”. So we all liked stuff. We liked people such as

Stanley Unwin; we liked mad things. Like there was a little film called The

Running Jumping & Standing Still Film that Dick Lester did with

Spike Milligan and we were attracted to those zany little things, which I think

gave us a personality as a group. And we would have fun with this.

The other

groups were just not like that. They were like guys who might work in a factory

or something. I remember once being in the dressing room in Hamburg and we knew

that the sax player of the bands was coming in and I happened to have a poetry

book with me, which my then girlfriend had sent me, and before he came in we

all sat round looking like we were all in deep contemplation as I read this

poem out. And the sax player came in, saw us all, with me reading this poem,

and he said, “Oh, sorry,” and very quietly put his sax away. When he left we

all burst out laughing. We knew we were different. We knew we had something

that all these other groups didn’t have. It gelled.

I

often think of things like this, as there are a million of them. I remember

making a guitar with George, going on hitchhiking holidays... I was a big

hitchhiking fan, so I would persuade George and John, mainly, to come on

holidays. So George and I hitchhiked one time to Wales. We went to Harlech and

stayed in a little place there and played a little gig, just me and George.

Then me and John went down to Reading, where my uncle had a pub. And we played

a little gig there as The Nerk Twins.

John asleep in Paris, October 1961 (photo: Paul)

And then me and John hitchhiked to

Paris... So all of these things, all these little things you might do as a kid,

but when you start thinking about them in detail...

And

I’m thinking now, there’s me and George, roadside, it’s a sunny day and we’ve

got a little camp thing, a little stove that I’d brought with me, and we’ve got

our methylated spirits to put in it. And then we go to the shop to buy some

Ambrosia Creamed Rice and we sit at the side of the road with this little

stove, boiling it up, sharing it with each other and thumbing down lifts. Once

we’d finished, we’d have sore thumbs. Just all of these memories, there are

just so many of them... So I do like to go on about The Beatles, because it was

magical. People say, “Do you believe in magic?” And I say, “I’ve got to.” And I

don’t mean, you know, Gandalf or wizardry or that sort of thing necessarily.

For me, it’s how life can be magical, these things that just came together. Me

and John knowing each other, the fact that both of us independently had already

started to write little songs... I said to him, “What’s your hobby?” I said, “I

like songwriting,” and he said, “Oh, so do I.” You know, no one I’d ever met

had ever said that as a reply. And we said, “Well, why don’t you play me yours

and I’ll play you mine.” That is most unusual and most fortuitous, the fact

that we should meet and get together.

When

did you first realise that you were a gang?

Hamburg.

We were mates. Me and John knew each other beforehand, from when I joined his

little group, The Quarrymen, so we were mates then, but not a gang. And me and

George were mates, having done all this hitchhiking together, living close to

each other... But it was only when, as a group, we got the Hamburg booking that

we started thinking like that. We were living on top of each other, so we

weren’t socially distancing, let’s put it that way. It is socially crowding. You’d

be in a room, the four of us, trying to find a blanket, or you’d be in the back

of van in the freezing British winter and the heating’s gone, so you had to lie

on top of each other... This is the kind of thing that makes friends of people.

You’re

not averse to showing yourself in public, are you?

When

I was a kid, I’d get on a bus, just going three or four stops, and get off,

look around. I remember years later, George Harrison said to me, “Do you still

go on buses?” And I said, “Yeah. I like it. I find it very grounding.” And I

actually do like it. I also like a nice car and I like driving too. But there’s

something about that, being ordinary... I mean, I know I can’t be ordinary, at

all – I’m way too famous to be ordinary – but, for me, that feeling

inside, of feeling like myself still, is very important.

The full interview is available to read here:

+ not entirely his fault. They keep asking him the same damn questions.