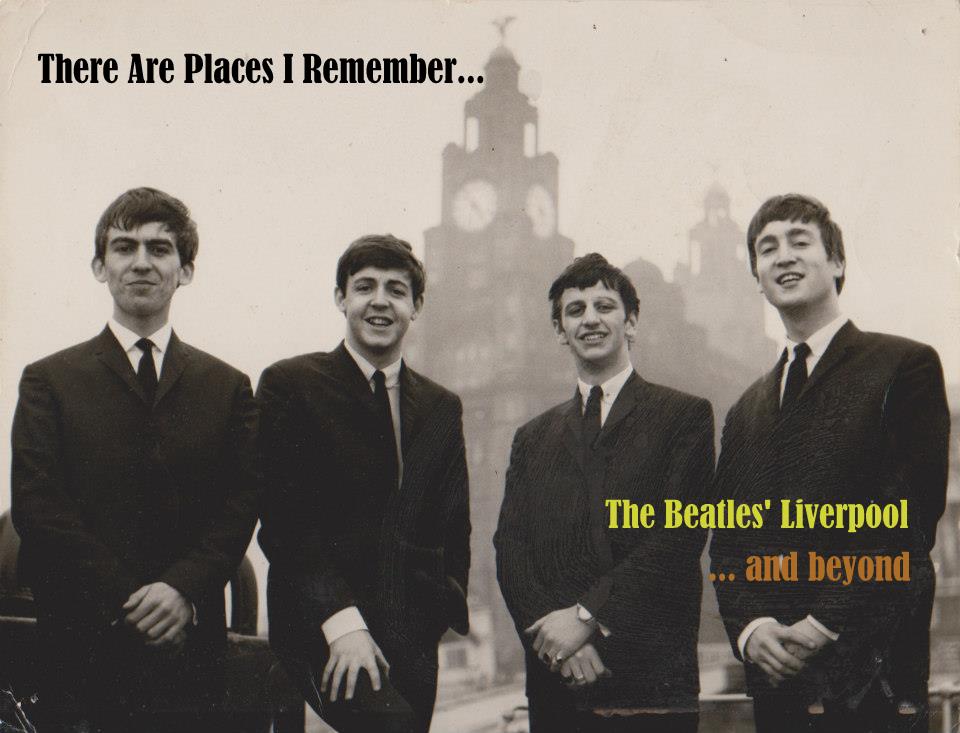

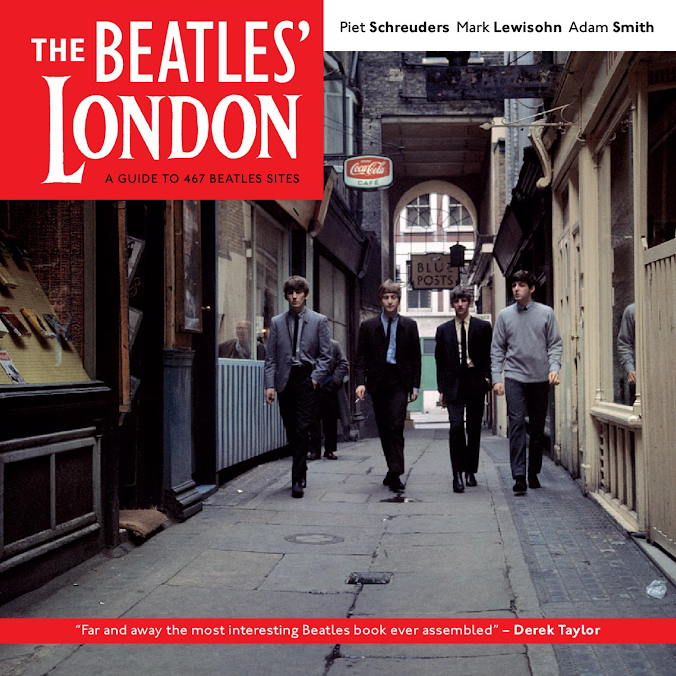

A recap: On Saturday 8 October 2022, I visited London with my fellow Beatles historian Steve Bradley to attend Evolver 62, Mark Lewisohn’s one-man show at the Bloomsbury Theatre. As the show didn’t start until 7.30pm we agreed in advance that it would be too late to travel home afterwards and decided to make a weekend of it. Armed with The Beatles' London, the indispensable guide to the 467 Beatles’ sites in the capital, Steve drew up an itinerary and we decided to try and visit as many as we could.

Of course, we didn't get anywhere near the magic 467, but I discovered that if you are prepared to spend two days walking 23 miles around the streets of London, you do manage to see quite a lot of them and get some quite magnificent blisters for your efforts.

We also had fun creating some Then and Now type comparison photographs whenever the opportunity presented itself, which I’ll post at the appropriate points.

I should also warn those of a nervous disposition that this post contains some notable but decidedly non-Beatle-y locations too.

And so, in the

order we visited them, here's part four:

3 Savile Row, W1

Until recently, 3 Savile Row was the clothing store Abercrombie and Finch.

Continuing our tour of the former homes of some of Britain’s greatest military commanders we ventured to Savile Row, world famous the world over for its traditional bespoke tailoring for men.

Number 3 was originally the home of Admiral John Forbes (1714-1796). Though he returned from war debilitated and unable to walk, Forbes still rose to the highest rank in the British Navy, a position he conducted from this house.

Upon his death the house was inherited by his son-in-law, 3rd Lieutenant William Wellesley-Pole, who leased the house to General Robert Ross (1766-1814). Ross is known Stateside as the British General who destroyed all the public buildings in Washington, including the White House, during the Peninsular War. 3 Savile Row was also the temporary home (twice) of the Duke of Wellington, Arthur Wellesley (1769-1852), notably in 1814 after returning from the Peninsular War following Napoleon’s exile.

Despite all three men being dead for more than the requisite twenty years there are no commemorative blue plaques for them on the front of number 3. There is only one, installed on 5 April 2019, marking an iconic musical event that happened in 1969. [3]

The Beatles’ London book describes the former headquarters of Apple Corps as ‘a mecca of the Beatles’ London, running EMI’s studios at Abbey Road a close second as a must-see attraction’.

That was written in 1994. 27 years later Peter Jackson’s extraordinary ‘Get Back’ film has undoubtedly renewed the interest of long-time Beatle fans', and brought a generation of new ones to Savile Row to visit this fine Georgian townhouse. With so many images from the film still so fresh in my mind I couldn't wait to see the building again having not personally visited for 33 years.

New Musical Express, 1 June 1968

The Beatles moved in on 15 July 1968. It was the third premises for their record label and associated companies which initially operated from a tiny office above the clothes shop in Baker Street before moving to 95 Wigmore Street in January 1968, where the other companies sharing the building complained about the noise. Buying the freehold on 3 Savile Row allowed the Beatles to make as much noise as they liked, renovate, and decorate it how they liked, meet with, and entertain whoever they liked, and relax by whatever means they preferred, within the comfort of their own offices, although as Paul would later admit in 'Anthology', being busted was something that they were all at risk of at that time.

Each of the Fabs had their own office, notably John and Yoko’s on the first floor, from where they conducted media and peace related events throughout the latter half of 1968 through to 1970. Neil Aspinall, Mal Evans, Peter Brown and Alastair Taylor, the Liverpool mafia who had been with the group since the start were also given offices.

Neil Aspinall: It was a big building. The record division was on the ground floor and the studio was in the basement. On the first floor there was a room for me and each of The Beatles. The next floor up from me was the press office, and after that I can’t remember. It might have been exciting for everybody else, and for people that came in from the outside, but for me it was hard work setting it up and there was always a lot of chaos. I was running Apple, but I have no idea what my position was – probably the lotus position. Running Apple at that time was hard work, in the sense that there were so many different ideas coming in, and people had different criteria for how Apple should be run and what it should represent, and who should be on the label and what colour the room should be decorated… On that level it was pretty difficult. Talking about colours is maybe a bit superficial, but it’s a symptom. There were big rooms at Savile Row, and somebody would say: ‘Why don’t you put a partition across the room so you can be here, and the secretary can be in the other room.’ So, you would get a partition built, and then the next day somebody else (a different Beatle) would come in and say: ‘What’s this partition doing here?’ and kick it down.

Someone would ask: ‘Do we need a press office?’ – ‘Yes, we do.’ – ‘Well, maybe we don’t…’ –

Derek Taylor was persuaded to return to the UK from America to run the press office.

Derek Taylor (Press Officer): There’s no doubt that by the end of 1968 (although I thought I was living for others; always martyring myself for the boys and all that). I was in my own egocentric way having an enormous amount of fun – ringmastering this circus for my own personal satisfaction, if you like. I was in a job that really suited me because it was chaotic. It was unmanageable, and yet it had a real press focus, and the work was getting done. But, had I been one of the boys, coming in as they did now again looking in on it, I’d have been shocked.

Derek behind his desk at 3 Savile Row. The photo behind him (right) shows the Beatles with Mavis Smith, Derek's assistant, backstage at the Liverpool Empire in December 1965.

Neil Aspinall: It was anarchy, really. Some of my memories are happy; some are not. I can’t say that I really enjoyed Savile Row that much.

John Lennon: And then I brought in Magic Alex, and it just went from bad to worse.

The steps outside the front door became the place for fans to congregate, with many spending all day and night waiting for the Beatles. Their devotion was later immortalised by George Harrison in his song ‘Apple Scruffs’.

A selection of fan photos showing the comings and goings at 3 Savile Row, and the author in October 2022 top left.

Neil Aspinall: We’d put an ad in the paper, saying: ‘Send us your tapes and they will not be thrown straight into the wastepaper basket. We will answer.’ We got inundated with tapes and poetry and scripts. We were overwhelmed by it all, in actual fact. (It was) ‘should we sign this artist, or shouldn’t we?’ Somebody would be signed because one person liked them, and then somebody else would be signed because somebody else liked them.

The Beatles never signed anyone on the strength of a sent-in tape but as Paul would later remember, at least people knew they were interested, and as a result they got James Taylor, Mary Hopkin and Badfinger.

Of course, the Beatles also did some fine work here, together and apart. There was a recording studio in the basement where 7 of the 12 songs appearing on the album ‘Let It Be’, as well as the B-side ‘Don’t Let Me Down’ were taped in January 1969 [2].

%20(45).heic)

Fortuitously we were able to access the steps down to the basement for a photo.

Three tracks on the album were recorded during the impromptu concert given by the Beatles up on the roof of 3 Savile Row at lunchtime on 30 January 1969. It turned out to be their last ever live performance.

The Beatles had a plan to play live somewhere and were debating where to go. As everyone who has watched 'Get Back' will know, there was endless talk of playing somewhere exotic, but in the end, they decided to play on the roof because it was much simpler than going anywhere else.

Paul: It was good fun, actually. We had to set the mikes up and get a show together. I remember seeing Vicki Wickham of Ready, Steady, Go! on the opposite roof, for some reason, with the street between us. She and a couple of friends sat there, and then the secretaries from the lawyers' offices next door came out on their roof.

[Author's note: Just before starting the first proper performance of 'Get Back' on the rooftop, Paul greets somebody off-camera. I'd pretty much settled on 'you alright Becky'? an acknowledgement /greeting which he says quickly in thick scouse, so it sounds like 'yorrite becky'? I now believe he says, 'alright Vicki'? as he spots her on the roof] [4]

Paul: It was a very strange location because there was no audience except for Vicki Wickham and a few others. So, we were playing virtually to nothing – to the sky, which was quite nice. They filmed downstairs in the street – and there were a lot of city gents looking up: 'What's that noise?'

Paul: In the end it started to filter up

from Mal (who would come creeping in, trying to keep out of camera range) that

the police were complaining. We said, 'We're not stopping.' He said, the police

are going to arrest you.' – 'Good end to the film. Let them do it. Great!

That's an end: "Beatles Busted on Rooftop Gig".'

Ringo: I always feel let down about

the police. Someone in the neighbourhood called the police, and when they came

up, I was playing away and I thought, 'Oh great! I hope they drag me off.' I

wanted the cops to drag me off – 'Get off those drums!' – because we were being

filmed and it would have looked really great, kicking the cymbals and

everything. Well, they didn't, of course; they just came bumbling in: 'You've

got to turn that sound down.' It could have been fabulous.

Neil Aspinall: The Beatles weren't businessmen and trying to run shops and record companies

and artists and publishing and buildings, as well as doing their own things,

did become very chaotic. A lot of money was being spent without people really

knowing what it was being spent on. So, it was a question of, 'Who is

going to do it?' I was running it on the basis of, ‘I’ll do it until you find

somebody who you want to do it.' I didn't want to do it myself.

Derek Taylor: The Beatles had been

looking for a 'leader with some status' in either the music business or the

City. They were looking for someone who could get a grip of it. They were

looking for 'the man' all the time.

George: To sort out Apple there

were a number of people who were interviewed at the time. I remember the story

about Dr Beeching, who shut down the railways of Britain – so they tried to get

him to come and see if he could shut down The Beatles as well. But he didn't

want the job, so Klein got it instead.

When Allen Klein came to Apple it was like that scene in 'The Rutles' when Ron Decline comes into Rutle Corps, and everybody jumps out of the window. He fired people - or some people ran away in fright- and then installed a bunch of his own men, who proceeded to control everything in the manner he wanted.

Neil Aspinall: Allen Klein brought in his own people and fired a lot of people who were

working at Apple. It didn't all take place in one day, but over a period of

nine months. For example, he would rather have Les Perrin (who was a PR man

with his own outside company who worked for lots of different people – he did

PR for The Rolling Stones and other people in the music business) than Apple

have its own press department. Ron Kass (Apple Records) went, Denis O'Dell

(Apple Films) went after Let It Be; Peter Asher went, Tony Bramwell went, Jack Oliver

went. It wasn't just slimming down – it was end of story.

Everything changed at Apple after

he arrived. It was a completely different situation. First and foremost, Paul

wasn't there. He totally disagreed with what was going on. But still, they went

into the studios and recorded 'Abbey Road' while Klein was around.

For the full picture of life inside 3 Savile Row see the books 'The Longest Cocktail Party' by Richard DeLillo (1972), and 'Apple to the Core: The Unmaking of the Beatles' by Peter McCabe and Robert D. Sconfeld (1972).

I really enjoyed seeing 3 Savile Row again, which looks comparatively unchanged since 1969. I won't be the only one who has stood outside and cast a glance skywards to the roof, just in case they're still up there.

33a Savile Row, W1

This was formerly The House of Nutter, a renowned tailoring shop, of which as mentioned above, there were - and still are - several on Savile Row.

Suitably named and ideally placed to catch the admiring eyes of those that frequented the madhouse at no. 3, it's no surprise that Tommy Nutter, a close friend of Apple's Peter Brown, tailored suits for the Beatles and their acquaintances. Paul McCartney married Linda Eastman wearing one of Tommy's suits. John, Ringo and Paul are wearing suits made here on the cover of their 'Abbey Road' album.

Ringo in his red plastic Tommy Nutter pants, 1969

Reluctantly leaving Savile Row, we turned right into New

Burlington Street, crossed Regent Street and entered Tenison Court at the end of which was the next stop on our trip, a non-Beatles location I'd specifically asked Steve to work into his itinerary. Luckily it wasn't a great diversion off the Beatle track, being directly behind Savile Row.

23 Heddon

Street, W1

This small, U-shaped side street off Regent Street was the location for a photo shoot one rainy night in January 1972 which produced the front and back covers of one of my all- time favourite albums, David Bowie's 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars'.

Apparently, this is the no. 1 David Bowie / Ziggy Stardust location in London, holding the same importance for his fans as the Abbey Road zebra crossing has for Beatles' fans.

%20(202).JPG)

For the front cover Bowie posed next to a pile of boxes outside no. 23, and inside a red London phone box for the rear.

In 1972 this was an industrial area. In 1996 the street was given a facelift and is now home to cafes and bars with outdoor dining facilities which reportedly have made it difficult for fans hoping to recreate their own Ziggy homage. We must have got lucky as I was able to position myself in an approximation of the front cover without any difficulty.

%20(195).jpg)

The rear cover photo showing Bowie inside a K2 telephone box was shot just around the corner. I was sad to discover that some unfortunate soul appeared to be living in the phone box. There was an office chair inside and the floor of the box had been lined with cardboard. It was covered in litter and smelt dreadful, but I had committed myself to recreating both the front and back shots used on the LP. Making Steve promise to take a couple of photos with a certain amount of hurry up involved due to my life being at stake, I took the plunge, held my breath and was in and out within seconds.

It was only later when writing this blog that I learned that Bowie's K2 model phone box had at some point been replaced by a modern blue box, and that in turn had been replaced by a traditional red K6 phone box in April 1997. You can see the difference in the way the glass panes are arranged in the door. Despite this phone box being something of an imposter, I noticed it hadn't dissuaded countless Bowie fans from covering it with messages and doodles. Would I have risked life and limp posing for the photo if I'd known in advance? Probably. The original K2 was reportedly sold to an American fan in the late 1970s.

Carnaby Street, W1

In many people's minds Carnaby Street was at the epicentre of 1960s Swinging London. This was where all the independent fashion designers of the time such as Mary Quant, Sally Tuffin, Lord John, Merc, Take Six and Irvine Sellars had premises alongside several well known boutiques including I Was Lord Kitchener's Valet and Lady Jane. Bands such as the Small Faces, The Who and the Rolling Stones shopped, worked and socialised here making it one of the coolest destinations in London.

Purists will no doubt point out that today's Carnaby Street is nothing more than a tourist attraction - and it was certainly very busy while we were there - but it's still home to all sorts of lifestyle retailers, including many independent fashion boutiques. As somebody so obsessed with 1960's music and fashion, especially mod culture, it pains me to admit that I've never visited before. I absolutely loved it.

The Rolling Stones' merchandise shop at 9 Carnaby Street which we visited.

9 Kingly

Street, W1

The Bag O' Nails was a live music club and meeting place for musicians in the later part of the Sixties.

Jamaican singer-songwriter Prince Buster outside the Bag O' Nails in 1967

In "Swinging Sixties" London, the Scotch of St. James and the Ad Lib clubs were the top draws for London's rock aristocracy, but the Bag O’Nails surfaced nevertheless as one of the hot clubs of the later part of the decade. Situated at 9 Kingly Street, it’s less than 100 feet from Regent Street – one of London’s busiest, most famous shopping streets – yet so inconspicuous it might as well be hidden anywhere.

Famously, Paul

McCartney met his future wife Linda Eastman at the club on 15 May 1967.

Paul: On

March 12th 1969 I got married to Linda. I had first met her a long time before

that. We actually met in a late-night

club I used to go to a lot in London, the Bag O' Nails. It was behind

Liberty's. I used to go to a lot of those places, because we'd finish gigs and

recording sessions about 11pm, and we'd be ready to have our evening off at

about midnight when everything was closed, so we either had to go to cabaret

places (originally, I went to places like the Blue Angel and the Talk of the

Town) or clubs and discos. I liked the Bag O' Nails because, though it was not

the most popular club, we could meet a lot of mates down there – music people

like Pete Townshend, Zoot Money, Georgie Fame. So, we could chat into the wee

small hours and have a few drinks.

One night Linda

showed up. She was in town photographing groups for a book called ‘Rock and

Other Four-Letter Words’. She'd been sent from America, and she'd just done a

session with The Animals. They'd come over to the club: 'Let's go out and have

a bevvie and a smoke.' So, she was sitting in an alcove near the band, which

was Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames – with Speedy Acquaye on bongos. They were

always a big favourite of mine. I saw her and thought, 'Hello...' When she was

about to leave the club, I stood up and said, 'Hello, we haven't met' – which

was a straight pull.

Then I said,

'We're going on to this next club called the Speakeasy. Do you want to come?'

And if she'd said 'no' I wouldn't have ended up marrying her. She said, 'Yeah,

all right.' So, we went on to the Speakeasy, and it was the first time any of

us had ever heard 'A Whiter Shade Of Pale'. We all thought it was Stevie

Winwood. It turned out to be the group with a very strange name – Procol Harum.

Justin Hayward

of The Moody Blues met his future wife Ann Marie Guirron there as well. Guirron

was a Liverpool girl and former girlfriend of George Harrison from the Cavern

days.

Notably, this is also the place where

Jimi Hendrix played his second London gig. Hendrix had been brought to London after being discovered by

Chas Chandler, a former member of the Animals, and he put the word out that a phenomenal guitar player from the United

States who could play the guitar behind his back and even with his teeth was in

town. His performance that night sent shockwaves through the assembled rock royalty who reportedly watched agog as Hendrix completely changed what it meant to be a rock guitarist.

"We were all hanging out at The Bag O’Nails: Keith, Mick Jagger. Brian [Jones] comes skipping through, like, all happy about something. Paul McCartney walks in. Jeff Beck walks in. I thought, “What’s this? A bloody convention or something?” Here comes Jim, one of his military jackets, hair all over the place, pulls out

this left-handed Stratocaster, beat to hell, looks like he’s been chopping wood

with it. And he gets up, all soft-spoken. And all of a sudden, “WHOOOR-RRAAAWWRR!”

And he breaks into Wild Thing, and it was all over. There were guitar players

weeping. They had to mop the floor up. He was piling it on, solo after solo. I

could see everyone’s fillings falling out. When he finished, it was silence.

Nobody knew what to do. Everybody was dumbstruck, completely in shock’."

Terry Reid, Vocalist with Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers

Doorway plaque

commemorating Jimi Hendrix's performance at the venue

It was one of the Beatles' favourite venues during the winter of 1966-67. After recording sessions their roadie Mal Evans, personal

assistant Neil Aspinall and unmarried, central London-based Paul McCartney, would head for the club. An entry in Mal Evans's diary from January 19 and 20 (1967) reads: I ended up drunk

in The Bag O'Nails with McCartney and Aspinall.

Clearly a club where a splendid time was guaranteed for all.

Broadwick Street (at Hopkins Street), Soho

On Sunday, 27 November 1966, John Lennon filmed his second appearance on the BBC2 ‘Not Only…But Also’ a popular comedy vehicle for Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. He appeared in a sketch as the doorman of an exclusive men's night club called the 'Ad Lav' (an obvious pun on the Ad Lib club) supposedly based inside an underground public convenience.

The BBC first broadcast the programme on Boxing Day, Monday 26 December 1966, with UK viewers getting their first view of the new bespectacled John Lennon.

%20(221).jpg)

While the toilets are still in situ it is evident that most of the surrounding buildings have been replaced since 1966. Note the Ivy restaurant on the right.

After another block or so we turned left into Berwick Street for another non-Beatle location.

(outside) 75 Berwick Street, Soho, W1V

The cover of (What's the Story) Morning Glory?, the second studio album by the Manchester rock band Oasis was taken here on the street outside Sister Ray vinyl in in 1995.

A seminal album of the 1990s, it was the album that defined the worldwide Britpop phenomenon. As of October 2018 it is the UK's fifth best-selling album and third best-selling studio album of all time, certified 16 x platinum with sales passing 4.94 million copies

Berwick Street was chosen because it was, and still is, a popular location for record stores, which I would love to have explored had we more time.

The two men passing each other are the DJ Sean Rowley and the album sleeve designer Brian Cannon (of Microdot). Ideally I would have liked Steve and myself to appear in the recreation (below) but somebody had to take the picture...

We retraced our steps to Broadwick Street and turned left onto Wardour Street. After a quick search for any A-bombs we took an immediate right into St Anne’s Court, visible on the above photo to the right of 'Gail's'. Here we found another Beatles' gem.

17 St Anne’s Court, Soho, W1F

%20(236).JPG)

In mid-1968, Trident Studios was the first independent recording studio in the UK to employ an eight-track reel-to-reel recording deck.

With Abbey Road Studios still only using four-track at the time, Trident's Ampex eight-track machine drew the Beatles here on 31 July 1968 to record their masterpiece "Hey Jude".

The band returned over the next few weeks to record some of the songs

for their 1968 double album 'The Beatles' (also known as the White Album) at

Trident – "Dear Prudence", "Honey Pie", "Savoy

Truffle" and "Martha My Dear".

Three weeks after the Apple Rooftop performance they were back at Trident, recording "I Want You (She's So Heavy)" on February 22, 1969, for the album 'Abbey Road'.

Individually the Beatles used Trident for their solo projects. On 29 September 1969 John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band recorded "Cold Turkey" at Trident after an earlier session at Abbey Road proved unsuccessful. Many of the overdubs for George Harrison's triple album All Things Must Pass, were recorded here in the summer of 1970, as well as Ringo Starr's 'It Don't Come Easy' single.

Many of the

Beatles' Apple Records artists used Trident Studios, including Badfinger, Billy

Preston, Mary Hopkin, Jackie Lomax and James Taylor.

Harry Nilsson recorded his classic version of Badfinger's "Without You" at Trident, and

portions of several of his 1970s albums. From 1968 to 1981, some of the most reputed artists used the studios for their recordings, including Manfred Mann, Elton John ('Your Song'), Marc Bolan / T. Rex, Carly Simon ('Your So Vain') the Rolling Stones, Free, Genesis, Peter Gabriel, Lou Reed, Black Sabbath and Dusty Springfield.

However, the blue plaque award goes to Mr David Bowie, who between 1970 and 1973 recorded the albums 'The Man Who Sold The World', 'Hunky Dory', 'The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars', and 'Aladdin Sane' as well as the iconic single 'Space Oddity', at Trident Studios.

Directly opposite the entrance to Trident is cramped alleyway called Flaxman Court. Paul McCartney, Mary Hopkin and a group of schoolgirls were photographed here during sessions for Hopkin's recording of 'Those Were the Days' in 1968.

In hindsight I shook have took the 'Now" photo in the same direction as the 1968 photo, facing towards the studio, but hopefully you get the gist.

We returned to Wardour Street (still no 'A bombs'), turned left and then took a right to Brewer Street, stopping on the junction with Rupert Street where we found a Beatles' location literally on every corner.[6]

Walkers Court at Brewer Street, Soho

Formerly the Doric Ballroom, the Raymond Revuebar was the creation of Paul Raymond. It opened on 21 April 1958 offering a traditional burlesque-style entertainment, which included strip tease, and proved popular with leading entertainment figures of the day. The venture was highly profitable and Raymond made over half a million pounds within the first ten years.

The Revuebar was one of the few legal venues in London to show full frontal nudity; by turning itself into a members only club it was able to evade the strictures of the Lord Chamberlain's Office which prohibited naked people moving about in public places of entertainment.

Even though homosexual acts between men were illegal at that time, the Revuebar also incorporated a Sunday night show aimed at a gay audience. By 1967, the venue was purely hosting striptease, and this is where the Beatles come in, visiting the venue purely for the purposes of making a movie, honest M'Lord.

Revuebar stills from 'Magical Mystery Tour' (Apple)

On September 18th 1967, the Beatles visited the Revuebar to film a scene for their 'Magical Mystery Tour' tv special, broadcast by the BBC on Boxing Day 1967.

John and George and other passengers from the coach trip were filmed watching Revuebar regular Jan Carson’s topless strip accompanied by the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band performing 'Death Cab For Cutie'.

In the final edit, a censored sign was superimposed over Carson’s bared Jeremys. The Beatles could never have got the boobs past the Beeb's controllers, the undressed breasts would have been suppressed, and in all likelihood the entire scene would have been cut.

'Magical Mystery Tour' was mauled by the critics. Paul was gracious enough to face the press in the aftermath, slyly referencing Jan's scene in his defence of the film, and using his hands to emphasize his point. Or perhaps not.

The Revue Bar, October 2022, photographed from Rupert Street. Note Brewer Street on the left. We'll be back here in a moment.

Paul Raymond's Revuebar closed in 2004 but as can be seen from my photo, at least some of the 1950s neon signage remains in situ.

Not being overly familiar with the geography of London before our trip, I was often surprised to discover that certain areas of seemingly little significance were visited more than once during the Beatles career, and some of the best known photographs of the group were taken in places only metres from each other, but several years apart.

The Brewer Street / Rupert Street area in Soho is a good example.

Brewer Street / Rupert Street

On 2 July 1963, the group posed for a series of Dezo Hoffmann photographs taken on the streets around Soho.

The weekday fruit and vegetable market on the corner of Rupert Street and Brewer street was one such location. Hoffmann took several photographs of the Beatles buying bananas on a stall outside 5-7 Brewer Street.

Note the sign for Brewer Street on the Adult Store, to the right of which is Walkers' Court and the Raymond Revuebar which the Beatles visited in 1967.

We then took a short walk to Old Compton Street to see five more Beatles' locations.

58 Old Compton Street, W1

This was formerly the premises of Westminster Photographic camera shop. On 22 April 1963 the Beatles and Dezo Hoffmann came here to view an 8mm film they had shot on Allerton golf course (Liverpool) on 25 March.

62 (nearest camera) and 58 Old Compton Street, W1

62 Old Compton Street, W1

Today, this and the adjacent number 60 Old Compton Street, are Balans, the 'infamous, outrageous and utterly unbeatable restaurant' which has been serving up good times in Soho since 1987. In 1962 it was part of the Golden Egg restaurant chain.

On 9 October 1962, John Lennon's 22nd birthday, the Beatles and Brian Epstein were on the second of a two day promotional visit, attending appointments with journalists across London arranged by Tony Calder, who was handling the publicity for 'Love Me Do'. In between interviews they all came here with Jeff Dexter, who was assisting Calder.

59 Old Compton Street, W1

One of the most important musical landmarks in the capital, this fish and chip restaurant was formerly the 2 i’s Coffee Bar, described in the 'Beatles' London' as 'the fulcrum of the teenage music scene in the late 1950s - the Cavern of its day'.

The name of the 2 i's derived from earlier owners, brothers Freddie and Sammy Irani, who ran the venue until 1955. It was then taken over by Paul Lincoln, an Australian professional wrestler known as "Dr Death", and Ray Hunter, a wrestling promoter and professional wrestler known as Rebel Ray Hunter. They opened it as a coffee bar on 22 April 1956. Tom Littlewood, a judo instructor who was initially working as the doorman, became the manager of the 2 i's in 1958.

A meeting between Littlewood and the Beatles' first Agent / Manager Allan Williams that same year inspired the latter to open his own 2 i's inspired coffee bar in Slater Street, Liverpool which he named the Jacaranda. Similarly, watching a news item on the the 2 i's spurred Mrs Mona Best in Hayman's Green, West Derby, Liverpool to open a coffee bar for her son Pete and his teenage friends in the basement of their house. The Casbah Club was born.

The 2 I's in the 1950s. A sign above the entrance read '2 i’s' between two Coca-Cola logos surrounded by musical notes with the words 'Coffee Bar' beneath all picked out in neon lights. This sign was changed for a more boring utility sign without the neon at some point in the 1960s (see below).[7]

The coffee bar allowed standing room for about 20 people, and had a serving counter with an espresso coffee machine, orange juice dispenser, and sandwich display case. A door at the back led to the manager's office, and a narrow stairway led down to a dismal and dark cellar about the size of a large bedroom, lit by a couple of weak bulbs. At one end was the small 18-inch stage made of milk crates with planks on top of them. There was just one microphone, left over from the Boer War, and some speakers up on the wall.

On Saturday 14 July 1957, the Saturday of the Soho fair the Vipers Skiffle Group were performing on the back of a flat-bed truck as it drove slowly around Soho Square, Wardour Street and Carnaby Street. When the truck stopped outside the 2 i's the Vipers went inside for coffee, still singing and passing the hat around. As they were leaving, Lincoln and Hunter asked them if they'd like to come back and perform in the evening, in the basement cellar. They agreed and became the first resident group at the 2 i's.

Within a couple of weeks the band's performances at the venue had begun to attract a large following through word of mouth. It soon won a clientele attracted because of its rock'n'roll music, and for a time became "the most famous music venue in England," and attracted talent spotters, record producers and music promoters such as Jack Good, Larry Parnes, Don Arden and George Martin, who signed the Vipers after watching them at the 2 i's. He bacame the first record producer to sign a skiffle group.

Several recording stars were discovered at, or performed at, the 2 i's, including Rory Blackwell; Tommy Steele; Cliff Richard and the Drifters / Shadows - Hank Marvin, Bruce Welch, Brian Bennett, Tony Meehan, Jet Harris, Brian 'Licorice' Locking; Vince Eager; Wee Willie Harris (Paul McCartney obtained his autograph outside the Liverpool Empire in March 1958), Adam Faith; Joe Brown; Clem Cattini (The Tornados); Eden Kane; Screaming Lord Sutch; Tony Sheridan; Lance Fortune; Albert Lee; Johnny Kidd; Ritchie Blackmore; Alex Wharton; Mickie Most (as the Most Brothers); Big Jim Sullivan; Joe Moretti; Vince Taylor; Duffy Power; Johnny Gentle; Derry and the Seniors; and Georgie Fame. Notable non-musical names among the 2i's clientele included Diana Dors, Michael Caine, Terence Stamp and Francis Bacon.

The authors of 'The Beatles' London' comment that the 2 i's café remained open through the 1960s and while they'd like to think the Beatles popped in during one of their visits down Old Compton Street, no visit was ever mentioned. More importantly, what the book doesn't mention is an absolutely crucial meeting that took place here which changed the course of the Beatles' fortunes for ever.

In March 1960, Allan Williams attended a concert at the Liverpool Empire starring Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran which prompted Williams to put on his own show at the Liverpool Stadium with the two stars. Williams struck a deal with the London music impresario Larry Parnes, to host the show on 3 May 1960. The show was a huge success despite the death of Eddie Cochran less than three weeks before. The supporting acts included Gerry and the Pacemakers and Rory Storm and the Hurricanes with Ringo on drums.

The success of the show was the beginning of a fruitful working relationship between Williams and Parnes, with the former providing Liverpool groups to act as the backing musicians for the latter's stable of solo artists, many of whom had been discovered in the 2 i's. Johnny Gentle was one, and Williams supplied the Beatles to back him on a tour of Scotland.

Another group promised work through the Williams - Parnes' arrangement was Derry and the Seniors. Booked to appear in a summer season in Blackpool, the deal went sour at the last minute when Parnes withdrew his offer. Having given up their day jobs in anticipation of the 'big time' the Seniors were suddenly left high and dry, and demanded that Williams do something.

With no work available in Liverpool, Williams offered to drive them down to London, heading to Soho where he hoped to hook up with his friend Tom Littlewood at the 2 i's. They were in luck, the resident rock acts at the café had the night off and the Seniors were given the opportunity to perform on the empty stage. What happened next was one of those extraordinary chance meetings with which the Beatles' story is littered, the sort of event a Hollywood script writer would usually have to invent to propel the plot only for it to be dismissed as so fantastical as to be unbelievable.

At the start of 1960, WIlliams and his business associate Lord Woodbine had found themselves in Hamburg where they'd become acquainted with Bruno Koschmider, the manager of the Kaiserkeller. Williams had suggested the German employ some British (i.e. Liverpudlian) groups in his club. In May, Koschmider made his way to England looking for groups, but instead of heading for Liverpool he went to London, and found himself at the 2 i's where he encountered Tony Sheridan and his backing band, offering them a contract to play at his club in Hamburg. They jumped at the chance, and proved so successful that a month or so later Koschmider returned to the 2 i's looking for another group, and it was here, 'by a million to one chance' that he met Allan Williams, watched Derry and the Seniors perform, liked them and offered them an engagement in Germany.

From here the story is well known. Looking for a rock act to play in his other club (the Indra), Koschmider asked Williams to put forward another group for consideration. Williams sent Koschmider the Beatles. The rest is history. Since his death the history books have been kinder to Allan Williams and it is now accepted that without Williams there would have been no Hamburg. Without Hamburg, there would have been no Beatles, or at least not the powerhouse act that went on to conquer the world. So, no 2 i's, no chance meeting between Koschmider and Williams, thus no Hamburg, and no Beatles.

63 Old Compton Street, W1

Arnold "Dougie" Millings was a London-based tailor known as "the Beatles' tailor".

Two doors away from the 2 i's, his shop - Dougie Millings and Son - was at 63 Old Compton Street, where he began designing for British pop stars such as Cliff Richard, Tommy Steele, and Adam Faith.

Millings – who was born in Manchester and trained in Edinburgh before moving to London to work as a cutter on Regent Street in the 1930s – would go on to make - according to the internet - most of the Beatles’ clothing, on stage and frequently off, for the rest of the decade. That’s some 500 suits.

Several of Millings garments have found their way into the archives of MOMA and the V&A, or are on display in Cleveland’s Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame, including a caped coat from the cover of ‘Help!‘; the velvet-collared, three-button suits the Beatles wore for their first US tour and landmark performance on The Ed Sullivan Show; and, of course, the round-collared, 'Pierre Cardin' style two-piece that would come to be known as ‘the Beatle suit’.

The Beatles on the first floor of Milling's shop on 2 July 1963 (Dezo Hoffmann)

The Beatles were regular visitors here in 1963 and Dezo Hoffmann photographed him in the shop on 2 July 1963, as part of his 'A Day in the Life of the Beatles' session which also took in many of the places featured in this blog.

Millings had a cameo in 'A Hard Day's Night', appropriately as a frustrated tailor.

76 Old

Compton Street, W1

Norman's Film Productions used to have an editing suite on the first floor here. The Beatles and editor Roy Benson came here between October and December 1967 to cut their 'Magical Mystery Tour' film. On 21 November 1967, the BBC cameras were present, filming the Beatles in the editing suite with the resultant film being used as a 'video' for the song 'Hello Goodbye'.

Steve and I then headed to the China town area of Wardour Street to see a number of locations that featured in Dezo Hoffmann's 'A Day in the Life of the Beatles' photo session on 2 July 1963.

24 Wardour Street, W1

Hoffmann photographed the Beatles in front of what was then the Kontact café while Ringo paid for two ice-creams. After the cafe closed the premises housed a bureau de change for a while before reverting to an ice-cream parlour of sorts, advertising itself as "the original and no. 1 Bubblewrap waffle house worldwide". The premises are directly opposite Rupert Court and the next location on our list.

27 Wardour Street, W1

In the 1960s this was Garner's, a restaurant specialising in seafood although the Beatles, who came here often in 1963, were reportedly fond of the crêpes. Hoffmann photographed them on the street in front of the restaurant while John and Ringo ate the ice creams just purchased from no.24. It's currently Hung's Chinese restaurant.

29 Wardour Street (2nd floor), W1

On the opposite side of the alleyway (Rupert Court - see below) to Garner's restaurant, is number twenty-nine Wardour Street. Dezo Hoffmann's photographic studio was situated on the second floor from 1960 until his death in 1986. He photographed the Beatles here on four occasions between April and July, 1963.

On Monday 22 April 1963 Hoffmann photographed them here wearing their new collarless suits, designed by Stuart Sutcliffe, inspired by Pierre Cardin, refined by Paul McCartney and cut by Dougie Millings. According to his son Gordon Millings 'It was the kind of thing that the like of Pierre Cardin was doing at the time, too. So that’s what (my father) came up with, these jackets with half-inch braiding on the edges, flared cuffs and a three pearl button-fastening, and tight, flat-fronted trousers with no pockets to keep the lines lean – and because Epstein said he didn’t want the band members to have pockets to put their hands in'. [8]

The Beatles with Dougie Millings during the Hoffmann photo shoot on 22 April 1963

Rupert Court, W1

This alleyway, between 27 and 29 Wardour Street, just below Hoffmann's studio, was the location for one of his best early photographs of the Beatles, in fact so good that it was chosen for the front cover of the Beatles' London Book (see at the top of this blog).

31 Wardour Street, W1

The top floor of 31 Wardour Street was the premises of Star Shirt Makers, another location visited by the Beatles during the Hoffmann session on 2 July 1963.

33-37 Wardour Street, W1

Here's somewhere I completely forgot to photograph! Right next door to the building comprising 27-31 Wardour Street is the former Flamingo Club. I did capture part of it in a general view of Wardour Street but I won't waste your time with it. Instead here's a photo of the club with the building containing Hoffmann's studio and Star Shirt Makers on the left.

As the plaque states, the club played an important role in the development of British rhythm and blues, modern jazz and later ska music, and as such had a wide social appeal. In the early 1960s you would find gangsters, pimps and prostitutes hanging out with American servicemen, West Indians, and musicians. John Mayall described the club as "a very dark and evil-smelling basement.... It had that seedy sort of atmosphere and there was a lot of pill-popping. You usually had to scrape a couple of people off the floor when you emerged into Soho at dawn...". In October 1962, the club was the scene of a fight between jazz fans Aloysius Gordon and Johnny Edgecombe both lovers of Christine Keeler, which ultimately led to the public revelations of the Profumo affair.[9]

By 1963, the Flamingo also became known as a centre of the mod subculture, where fans and musicians of both jazz and R&B music would rub shoulders. Unusually, it employed black musicians and DJs; it did not have a drinks licence, and illicit drug-taking was commonplace and generally tolerated by the police. It became recognised as a meeting place for famous musicians including members of the Who, the Small Faces, the Rolling Stones, Jimi Hendrix and many others.

All four Beatles came here on occasion, one being 6 September 1963 when they were accompanied by Robert Freeman, Peter Blake and his wife Jann Haworth. Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames were performing that evening in the upstairs part of the building, known as the All-Nighter Club (and later ther Whisky-A-Gogo).

On 6 August 1965, Brian Jones and Paul McCartney (with Jane Asher) attended a performance by the Byrds.

Through the resulting melting pot of music, fashion and social cross-culture, the Flamingo played a small but important part in the breakdown of racial prejudice in post-war British society and the club was one of the first UK venues to introduce ska music to a white audience, with performances by Jamaican born musicians such as Count Suckle.

Incidentally, I missed the Marquee Club at 90 Wardour Street too. Justification enough for a return visit in Spring 2023!

7 Leicester Place, WC2H

_(83).jpg)

The Ad Lib Club was a nightclub on the fourth floor of 7 Leicester Place over the Prince Charles Cinema in London's Soho district. It opened in late 1964 and according to Mark Lewisohn it soon became the club 'most strongly associated with The Beatles', who had their own table.

The Beatles ended their evening at the club following the premiere of 'A Hard Day's Night' on 7 July 1964. Ringo proposed to Maureen Cox here in January 1965.

Reportedly, the Ad Lib was one of the relatively few places that John felt he could go without being unduly bothered which is why, as Kenwood suggests on his excellent blog it was probably why the participants in what George Harrison referred to the 'Dental Experience' came here one particular evening in 1965. .

On or about 8 April 1965, John and Cynthia Lennon, George Harrison and Patti Boyd accepted a dinner invitation at the home of their 'wicked dentist', John Riley. After the meal Riley served them coffee laced with LSD aiming to be the first person to 'turn on' The Beatles.

Later that night they were planning to go to a London nightclub called the Pickwick Club to watch their friends playing (Paddy, Klaus and Gibson). When the two fabs decided it was time to leave, Riley became insistent that they stayed... or at least until they'd finished their coffee.

They finished their coffee and again George suggested they leave at which point the dentist said something to John, who turned to George and said 'We've had LSD'. John later recounted that it was all the thing with the middle-class London swingers who'd heard all about it and didn't know it was any different from pot and pills. He gave us it, and he was saying, 'I advise you not to leave.'

At the time the drug was little-known, and still legal, but George sensed that Riley was trying to get them to stay for something seedy, perhaps thinking it was an aphrodisiac. As Harrison remembered in Anthology: I remember his girlfriend had enormous breasts and I think he thought that there was going to be a big gang-bang and that he was going to get to shag everybody. I really think that was his motive.

It was definitely time to go. George drove them to the Pickwick club (with the dentist following in his car) parked and went in.

No sooner had they sat down and ordered their drinks when the drug started to kick in. George remembers 'the most incredible feeling' coming over him - 'a

very concentrated version of the best feeling I'd ever had in my whole life'. He felt like he'd fallen in love with everything and had the overwhelming desire to go round the club telling everybody how much he loved them - people he'd never seen before.

George: One thing led to another, then suddenly it felt as if a bomb had made a direct hit on the nightclub and the roof had been blown off: 'What's going on here?' I pulled my senses together and I realised that the club had actually closed - all the people had gone, they'd put the lights on, and the waiters were going round bashing the tables and putting the chairs on top of them. We thought, 'Oops, we'd better get out of here!'

We got out and went to go to another disco, the Ad Lib Club. It was just a short distance so we walked, but things weren't the same now as they had been. It's difficult to explain: it was very Alice in Wonderland - many strange things.

In 1970 John had memories of the night very consistent with Georges. On their arrival at the Ad-Lib: We thought when we went to the club that it was on fire, and then we thought there was a première and it was just an ordinary light outside. We thought, 'Shit, what's going on here?' And we were cackling in the streets, and then people were shouting, 'Let's break a window.' We were just insane. We were out of our heads.

George: I remember Pattie, half playfully but also half crazy, trying to smash a shop window and I felt: 'Come on now, don't be silly...' We got round the corner and saw just all lights and taxis. It looked as if there was a big film première going on, but it was probably just the usual doorway to the nightclub. It seemed very bright; with all the people in thick make-up, like masks. VERY STRANGE.

We went up into the nightclub and it felt as though the elevator was on fire and we were going into hell (and it was and we were), but at the same time we were all in hysterics and crazy.

John: We all thought there was a fire on the lift: it was just a little red light; we were all screaming, 'AAAAAAAARGH!' all hot and hysterical. And we all arrived on the floor (because this was a discotheque that was up a building), and the lift stops and the door opens, and we were all, 'AAAAAAAARGH!' and we just see that it's the club,

Ringo: I was actually there in the club when John and George got there shouting, 'THE LIFT'S ON FIRE!'

Interestingly, Kenwood's wonderful blog (with input from Julian Carr) reports that there was an actual fire in the Ad-Lib club on 5 November 5, 1964 resulting in its temporary closure for repair and renovation due to extensive damage. It being their favoured club of the moment, the Beatles would certainly have known about the fire, and it would not have been long re-opened at the time of their 'dental experience'.

Was this knowledge, coupled with their chemical intake, the source of their red-light related paranoia?! [ 10]

John: We walk in and sit down and the table's elongating... I suddenly realised it was only a table, with four of us around it, but it went long, just like I had read, and I thought, 'F*ck! It's happening.' Then some singer came up to me and said, 'Can I sit next to you?' I said, 'Only if you don't talk,' because I just couldn't think.

IT WAS TERRIFYING, but it was fantastic. I did some drawings at the time (I've got them somewhere) of four faces saying, 'We all agree with you!' - things like that. I gave them to Ringo, the originals. I did a lot of drawing that night.

They all went to bed, and then George's house seemed to be just like a big submarine I was driving.

Let that be a warning to you. Never accept a dinner invitation from your dentist. That said, who goes to their dentist's for dinner?

While Steve rested his weary leg, I ventured on into Leicester Square (very busy, seemed to be something going on) and Cranbourn Street which runs off it.

1 Cranbourn Street, WC2

Cranbourn Street has two adjacent venues associated with the Beatles, and particularly Paul McCartney. Though my photograph (below) doesn't really do it justice, the building in the centre of the photo with the canopy - now a Vue multiplex - was formerly the Warner Cinema.

%20(1).jpg)

Paul mobbed at the Warner Cinema, 18 December 1966

On Sunday, 18 December 1966) Paul and girlfriend Jane Asher attended the world premiere of The Family Way, a British comedy-drama film about two young newlyweds whose marriage has yet to be consummated. Directed by Roy Boulting, the film starred Hayley Mills, Hywel Bennett, John Mills, Marjorie Rhodes, Murray Head and Avril Angers. Paul had written the theme music.

The former Warner Cinema (centre, with canopy) with the Hippodrome to the right of it.

10 Cranbourn Street, WC2

Designed by Frank Matcham, the impressive London Hippodrome was built in 1900 as a circus and water show, an elaborate stage-spectacle impossible in any other theatre. The floor could be lowered and the resulting 'tank' filled with 100,000 gallons of water! All manner of performing creature appeared in the circus ring from elephants to lions to rattle snakes.

A later rebuild enlarged the stage and used for musical revue, musical comedy, and ice shows. By the 1950s the Hippodrome was hosting variety shows with performers such as Max Bygraves, Alma Cogan and Lonnie Donegan topping bill. It closed on 17 August 1957.

The actor Albert Finney with Alma Cogan at the Talk of the Town on 31 January 1961 (Evening Standard)

The Talk of the Town in 1961, headlined by the Beatles' favourite American group, Sophie Tucker

In 1958 Bernard Delfont and his partner Charles Forte ripped out the interior and converted the theatre into a large restaurant/nightclub they called “The Talk of the Town”. With theatre producer and director Robert Nesbitt and the architect George Pine, they hoped to create a sort of restaurant intimacy combined with a theatre experience that would put London not merely abreast of the times, but ahead of them.

The former gallery was closed off with a false ceiling and the dress circle became a dining area with two staircases leading down to a dance floor and the main part of the restaurant. There were 800 covers and the price in 1958 for a three course dinner and two shows was just two guineas.

The first show at the Talk of the Town began at 9.00pm and was a dance spectacular in the style of the Folies Bergère. At 11.00pm came the star of the show - Eartha Kitt - appearing to the audience by rising up from beneath the stage in a vintage Rolls Royce. [10]

This was a favourite haunt of Paul McCartney and Jane Asher, who came to dine while watching the top performers of the day, including Diana Ross and the Supremes who had a residency here in February 1968.

A Talk of the Town Souvenir Programme from early 1968 signed by Paul McCartney.

On 15 March 1970 Ringo filmed a promotional video for the title song of his Sentimental Journey album on the 'Talk of the Town' stage. Note the back projection showing his album cover / local pub, The Empress (centre) and his final Liverpool home, Admiral Grove on the right.

So that's part four of our London trip, a post so long that even Peter Jackson would edit it. Part five coming soon (we might even get to Mark Lewisohn's show in the next installment!)

Notes

%20(180).JPG)

%20(45).heic)

%20(221).jpg)

%20(229).jpg)

%20(236).JPG)

_(84).jpg)

_(83).jpg)

%20(1).jpg)

%20(177).JPG)

%20(202).JPG)

%20(195).jpg)

%20(215).JPG)

%20(61).heic)

%20(253).JPG)

.jpg)

%20(278).JPG)

%20(353).JPG)

It's also enlightening that absolutely every BEFORE photo on location looks a lot more sightly than every AFTER photo.

ReplyDeleteIt's always the way.

Deletewhere this quote from Paul was taken from ? :

ReplyDeletePaul: It was good fun, actually. We had to set the mikes up and get a show together. I remember seeing Vicki Wickham of Ready, Steady, Go! on the opposite roof, for some reason, with the street between us. She and a couple of friends sat there, and then the secretaries from the lawyers' offices next door came out on their roof.

From the "Beatles Anthology" book.

DeleteI enjoyed reading your post about walking the Beatles' London tour in October 2022. The Beatles are such an iconic band with a rich history, and it's fascinating to learn about the places where they lived, worked, and performed.

ReplyDeleteI noticed in the comments section that someone had asked about Walmart's airbed policy, which seems like an unrelated topic to your post. However, I understand how frustrating it can be to deal with a faulty airbed and not know what to do about it.

If anyone has any experience with Walmart Airbed Policy or can provide any helpful tips, please share them in the comments. It's always helpful to have a community of people who can offer support and advice on a range of topics.

Thank you for sharing your Beatles knowledge and experience with us, Beatles Liverpool Locations! I look forward to reading more of your posts in the future.