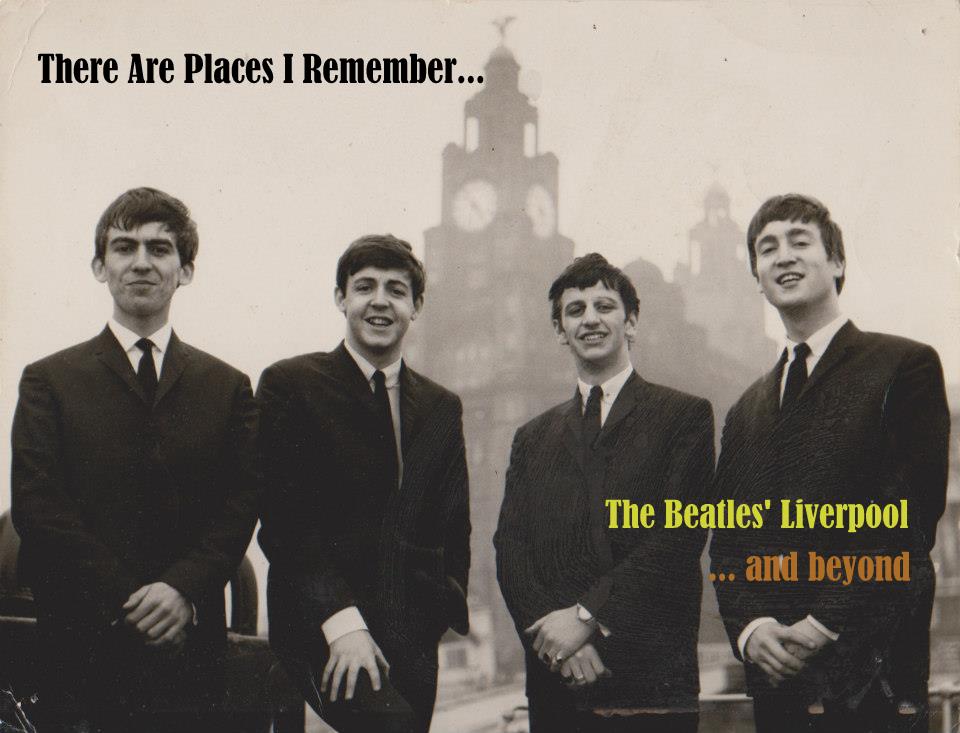

"Portrait of Paul"

An interview with Mike McCartney for Woman magazine, Saturday, August 21, 1965.

This 1965 magazine article has recently been brought to my attention. Mike talks at length about growing up in Liverpool with his brother Paul, the loss of their mother Mary, Paul finding solace in music, meeting George and John, and the impact Paul's enormous success has had on family life.

Reading it now it's clearly a precursor to Mike's 'Thank U Very Much' book and contains many of the same tales, some of which have undoubtedly evolved with the passage of time:

Paul was Mr. Bathroom and I was the Lord Mayor and we were playing a game called Winning Prizes with our five-year-old step-sister, Ruth.

This was the other day in the dining room at home. I was stretched on a settee drawing cartoons and waiting for the results of the game. As Lord Mayor all I had to do was distribute the prizes.

Mr. Bathroom was working out his sums with a pencil stub. And getting them all wrong! Ruth was getting hers all right. They handed me their finished papers and I marked Mr. Bathroom with a big 0 and I gave Ruth 100, which was thoroughly deserved, because she’s only about seven inches high. Then I handed them their prizes. Ruth got a boomerang and two chocolate buttons. Mr. Bathroom got one chocolate button and a boot – even if he had got all his sums wrong – because he was such a spiffing sport.

You could say that’s typical of my brother Paul – always kind to the ladies, whatever their age. Paul’s always been a charmer. As far back as I can remember, he’s been considerate to girls, even horrors.

I remember one evening years ago – Paul couldn’t have been much more than ten at the time – there was a knock on the door. Paul got up and went to the window to see who it was. Suddenly he turned and streaked up the stairs like Winnie the Pooh on fire. We thought he had gone nutters. Not that that was anything in our house – for years our dad was convinced that both Paul and I were nutters. He couldn’t get our sense of humour, that was all. He thought we were “daftheads.” Anyway, this time even I thought Paul had gone crackers.

He stood at the top of the stairs and whispered: “Tell them I’ve got measles or something. Anything!” We’d no idea what he was talking about. But Dad caught on when he opened the door. They weren’t much all right – three tattyheads who wanted Paul to come out to play. So you couldn’t blame Paul. But the point I’m trying to make is that he wanted to be kind and spare their feelings.

Does the fact that Paul used to have to hide from girls, even when he was as young as that, surprise you, viewers? Actually, Paul’s been involved with girls one way or another ever since he was eight! I envied him – all the kids called him the Boy Casanova of Speke (which was the Liverpool district where we lived). His big secret? He wasn’t shy. Also he was good-mannered. Mum had always made a point of this – being considerate to others. Not that she wanted us to be softies – she knew better than to try and bring us up as a couple of cissies in a place like Liverpool – but she was determined not to have two tearaways on her hands.

The first girl Paul ever really dated seriously was called Val. Oh, it was real luv and all that. She had long hair, had Val. And Paul loved long hair. Still does, in fact.

It’s hard to imagine Paul believing that a girl couldn’t be interested in him. But when he met Val, he honestly didn’t believe that a girl could feel about him the way he felt about her. He seemed to think that girls didn’t have any feelings.

He saw Val coming home on the school bus every day. He never sat beside her or carried her books or anything like that, so far as I can remember. All he used to do was to sit and gaze at that long hair. “You know, she’s really great,” he told me. “I don’t half fancy her.”

Although he could chat up most girls quite easily, somehow he didn’t have the nerve to talk to Val. Perhaps all his confidence was surface stuff and when it came to the crunch, he could be as shy as anybody. Then one night word came along the grape-vine that Val like him. You should have seen the way he went on – he was completely knocked out!

He took Val out once or twice – to the cinema, visiting friends – that sort of thing. Then the whole affair suddenly fizzled out.

Paul is my elder by a year and a half. My earliest memory of him is the day he began hitting me over the head with his golliwog [stuffed toy]. I don’t know why he attacked me, because he loved that golliwog and it soon became clear that the golly was going to come off second-best. Actually, apart from this, our relationship has always been fairly good although, when we grew up, we used to thump each other about a bit. Had to let off steam, I suppose.

The first house I remember was a terraced one, owned by the Corporation, in Speke. Dad was a cotton salesman, mother the district midwife. It was a neat little house, beautifully kept by Mum who was out to do her best for us all. But she didn’t fancy the house or the district all that much. It was she, I don’t doubt, who was behind all the moves we made in the next few years – we moved house no fewer than five times. Each time the new house was a little bit better than the one before; the district so-called more respectable than the one we’d left. Mind you, they were all ordinary terrace houses. But the gardens got bigger and bigger. And as neighbourhoods got “better” the people in them talked less and so our circle of friends grew smaller and smaller.

Mum and Dad were hard-working and ambitious – the McCartney family was determined to move up in the world. Mum always drummed in to us the need to be clean and well-mannered and to take care of our appearance and so on. And she made sure that we two scruffs always had good, neat clothes.

Two views of 12 Ardwick Road. The waste ground opposite with beehive and shark infested lime pit was never built on. Today it's a harmless looking field.

We were always loyal to each other, Paul and I. I remember once we fell foul of a swarm of bees. Opposite our house was a bit of waste ground and somebody decided he’d keep his bees there. When Paul, ringleader of our bunch, saw the hive, he decided we’d find out what was inside it.

Daft though we were, we had enough sense to circle warily about the hive first. Paul must have suddenly got a few brains from somewhere because he decided not to go any nearer. Then his brains must have fallen into his boots because he yelled: “Let’s stone it!”

That did it! As a shower of bricks knocked the hive spinning, a swarm of angry bees suddenly emerged and bombed their way towards us. We all bolted. All except Paul, that is. I heard him yelling and turned to see him beating the air like crazy. I think the bees picked on him because of his long hair – even in those days it looked llike a baby mop. Anyway, without stopping to think what I was doing, I turned back to help him. Very nasty. I saw all the bees swarming over his locks and so I lashed out at them. I must have been a real softhead – for at once they turned and attacked me!

“Run for it!” I yelled and we belted for home. Eventually we got inside and slammed the door behind us, locking out the bees. We’d been stung perhaps a dozen times each – so it was no joke. We were a pair of sick little sting-heads for some time after that, I can tell you.

I once saved Paul’s life, viewers (but we’re quits, he later saved mine)! He was ten at the time and I was about eight. One day we found a lime pit which had filled with rain and turned into a small pond. Some workmen had left a plank balanced across it and, needless to say, we had to walk across it.

But who was going first? You’d have thought there were sharks in that old lime pit!

“Go on, you go, Paul,” I said, not liking sharks.

“No, you go,” he urged. “After all, if you fall in, I can always pull you out!” Paul wasn’t so simple, really – he only gave that impression.

In the end we decided we’d both go together. That meant disaster. We were about halfway across when the plank began to sway dangerously and suddenly Paul lost his balance and fell in. The plank then wobbled so much that I fell in after him.

We might have drowned – really! After all, we weren’t very big – no more than up to your ankles. Not that we were out of our depth – but when we tried to clamber up the sides of the pit, we found them too slippery. If we’d got into a panic, we should probably have drowned – but we were so scared that we actually behaved quite calmly. I remember digging my fingers into the soft, slippery earth and getting a grip on a big stone or something and then starting to haul myself out. But when I turned to see how Paul was doing, I saw that he had fallen back, spluttering and gasping, and his head was going under. I grabbed him by the collar and held on. He caught hold of my arm and clung to it. We stayed like that until a neighbour, hearing our cries, rescued us.

That night, by way of reward, Dad gave us the hiding of our lives. We went to bed crying and lay with our heads on the pillows sobbing bitterly. I was prepared to regard the hiding as just punishment. But not Paul. He dried his eyes and began to think out ways of getting revenge on Dad. Some of them sounded like ideas out of a Chinese torture book, only dafter. Finally, he said: “If I could, I’d take Dad up to 15,000 feet in a plane, dig a hole, fill it with water, and drop him in!” You can’t say he didn’t have imagination!

On the other hand he could be very casual about important things, our Paul. Such as saving my life, for instance – very important that. It happened one day in the Woolton baths. I couldn’t swim very well at the time and got out of my depth. I had gone blue in the face when he managed to haul me out. I spluttered something about saving my life – I see everything in dramatic colours – but all he said was: “Oh, it gave me a chance to practise my life-saving lessons!” Impudent life-saving rascal!

We didn’t have a lot of luxuries or expensive treats when we were kids, Paul and I. I remember a big thing was when Mum called at school one afternoon and got us off early from our mid-day nap in order to take us to the circus. I suppose that’s the kind of treat most kids can remember.

Another time was when Dad came home one evening hiding something behind his back. It wasn’t long after the end of the war and most things were still scarce. I remember Dad looked very pleased with himself when he showed us what looked like a bunch of bloated yellow fingers. “Look, boys,” he said triumphantly, “bananas!” We hadn’t the faintest what bananas were and I saw the disappointment on Dad’s face. “Try them,” he said. “You’ll love them!”

Poor Dad! We munched one each and then Paul made a face. “Ugh!” he said, shaking his head. “Horrible!”

We were a terrible pair about food, actually. Paul would never eat cauliflower or sago pudding and neither would l. When I was forced to eat sago pudding at school once, I got sick. Paul’s imagination started working immediately. “Pretend you’ve got jaundice,” he suggested. “Go all yellow and scare everybody!”

Paul loved everything sweet. He’d eat sweets and cakes until he exploded if somebody didn’t stop him. Toleration and Moderation, young Paul! He ate so much sweet stuff that he grew very fat in his early teens. I used to call him Fatty. He didn’t like that, of course. But he was a fatty. Weren’t you, Fatty?

It was a nuisance to him all that fat. One day it got us both into trouble. We used to do our fair share of knocking off apples in a nearby orchard – it was called Chinese Orchard* and it was in Horseshoe Woods. That day there were four of us altogether – Paul and I, a neighbouring tearaway called Roger the Dodger – and our shaggy dog, Prince.

We were doing very nicely when Prince suddenly started barking. We turned and saw a man lurching towards us, shouting. We all dropped the apples and ran. Prince got clear and Roger the Dodger vaulted the fence like a greyhound and I wasn’t far after him. But Paul, because of his weight, got stuck on top of the fence and couldn’t get over in time. The man grabbed him and yelled after us: “Come back, all of you or I’ll take it out on your pal!” Trust me, of course. Like a nutter, I ran back. The man locked us both up in a dark shed until Dad came for us. This time he simply read us the riot act – which made a greater impression on us than half a dozen hidings.

The McCartneys were steadily growing more prosperous. Dad was now earning more money and one day he bought us two bikes – flashy jobs with dropped handlebars which sent the other kids in the district green with envy. Not that we remained in that district very long – we were soon on the move again. While Mum worked to give us a better home, Dad went to a lot of trouble to give us some fun. He fixed up an arrangement of earphones in our bedroom so that we could lie at night and listen to the Goons and other comedy shows.

Paul was absolutely knocked out by all this. He couldn’t hear enough of these comedy shows. He’d keep the earphones on until he fell asleep – then he’d be wakened up in the middle of the night when some French or German programme began booming in his ears! Next day we’d run over the comedy show we’d been listening to the night before, mimicking the different parts.

We were

fairly normal boys, really. Paul, I suppose, was always a shade quicker to

resent authority or discipline than I was. We didn’t have a grudge – but we had

our own individual ways of looking at life and our own individual ideas on what

was interesting and how to do things.

Paul was good at most school subjects and before he became one of the Beatles his great ambition was to be a schoolteacher. Not many people know that he has “O” levels in Spanish, German and French. He was never out of the A stream at school and once won a book prize from the Lord Mayor of Liverpool.

What interested him most was art – he was crazy about painting. Still is, in fact. At times we thought we had a boy Michelangelo on our hands. If you left a newspaper down for a second, Paul would pick it up and start drawing all over it. Nothing was sacred. At one time he used to draw nothing but horses. Then it was faces. He went through a “pastoral period” when he would draw nothing but woods and outdoor scenes. Nowadays he draws guitars, drums, other musical instruments – and money from the bank. The biggest influence in arousing his interest in art was his art mistress at school. When she discovered he had some talent, she gave him every encouragement. And he was always top of his art class.

We both have an aptitude for art. But Paul is the painter. I’m the drawer. Both of us paint and draw, of course – but I’ll never be as good a painter as Paul. His smooth brushwork has always taken him far ahead of me. He draws very funny cartoons, though. I remember one he sent me from Germany when the Beatles were first touring there before they became famous. It showed a bus inspector in the foreground talking to his mate and a single-decker bus going past in the background. There was this little conductor bloke standing on the roof of the single-decker and the inspector is saying: “You know, I don’t think our Charlie’s got the hang of these things yet.”

Paul is still very serious about his painting and his room at home is decorated with his efforts. His most ambitious work is an eight foot tall portrait of a bizarre, cubist-looking woman, done in different sections. She’s got a great big colourful nose. One of his best works is a self-portrait – and it is very, very good.

***

Everybody was quite confident that Paul would pass the eleven-plus – for Mum and Dad thought of him as the brains of the family. And of course, he didn’t let us down, because he was a natural at exams. When I passed in my turn, it was so unexpected, apparently, that Mum burst out crying – I think the idea that she had two “intelligent” sons was too much for her! They say sensitivity often goes with intelligence and certainly I’d say this was true of Paul. Although on the surface he tried to give the impression that he was a fairly tough, swashbuckling, mildly-tearaway character, underneath there was a great deal of thoughtfulness and real tenderness.

The other thing, besides art, that interested Paul was nature study. Here again it was a question of having his interest aroused at school. There was a school rabbit and it was one of the jobs of the nature class to march across the countryside to a farm a few miles away to get straw for this rabbit. During these tramps, Paul would poke into streams and ponds and study water-rats, moles, field-mice, fish – all sorts of things. Eventually we persauded Dad to get us a rabbit of our own. Dad was a spiffing brick – he got us one each. I don’t remember what kind of rabbits they were – all I can remember is that they had long ears and big teeth. I had the white one and Paul had the black one.

We christened one Bertie and the other Harry. What we didn’t know was that Harry was a girl. One day we came home from school to find that Harry had a litter of rivulets, or whatever you call rabbit’s babies – maybe “rabbies” – and that Bertie, in a fit of jealous rage, had stamped upon them all and killed them.

Paul and I cried and cried. Particularly when we had to pick the babies up and get rid of them.

Seven Ponds, Speke**

Paul then got a bug about tadpoles. “Is it possible to make a pond, Dad?” he asked one day.

“What for, son?” asked Dad.

“To raise tadpoles,” replied Paul.

Dad was

always very good at trying to supply anything we wanted – particularly if he

thought it would be of an informative or educative nature. A few days later he

dug a big hole in the back garden and sank a beer barrel in the space. Then he

left us to fill it with water.

Paul got a lot of frog-spawn from somewhere and dumped all this into the barrel. For weeks he lived for nothing else but that spawn. The moment he came home from school, he’d be out into the garden, stuffing his face down into that spawn to see how it was getting on.

“They’re

getting tails!” he’d yell at me and then I’d go and look at the messy stuff. I

couldn’t understand what was exciting him.

“Look, there’s one with a body!” he’d point. All I could see was stuff that looked like a whole lot of dirty marmalade.

Then one

day he ran into the house yelling blue murder.

“They’re getting away!” he was shouting. “They’re running off into the fields!”

Mum and I ran out and there was a horde of frogs jumping and leaping about all over the place. We managed to grab one or two and hold on to them for a moment or so but the minute we set them down again, off they went, into the bushes and hedges. In a very short time, Paul’s pond was completely empty! You should have seen his face! It would have made you laugh and cry at the same time. He had never counted on his spawn turning into real live frogs – neither had the frogs!

I can’t remember exactly when Paul turned into a musician. But it was certainly when he was still in his early teens. There was quite a bit of musical tradition in our family. Dad, in fact, used to have his own jazz band – Jim Mac’s Jazz Band – which was well known at one time in the Liverpool area, and he was an accomplished pianist. He had always hoped that one of us would become a musician but unlike some fathers, he had never made any attempt to force us into it.

But when Paul began to show an interest in Lonnie Donegan, Tommy Steele and the other early pop artistes, I think Dad saw his chance. Anyhow, he bought Paul a guitar, and, as always with Dad, he made sure it was a good one – it cost £18.

Paul becoming a musician was sheer torture for the rest of us – at least to begin with. I hate to think how near the world came to losing one of its Beatles even before it knew it had any Beatles at all. Plunk, plunk, plonk! If there was a wrong note around, Paul was sure to find it! “Oo-er!” he used to say.

Then he suddenly realized why he wasn’t doing well. “I’m left-handed,” he said. “I’m all on the wrong side.”

And just

to show he wasn’t as daft as he looked, he set to work to turn the strings

right around to suit a left-hander. From then on, I’m glad to say, we got a few

more plunks and a great many less plonks.

Finally he had enough confidence to take the guitar with him when we both went to camp with the Boy Scouts. In the evenings, we’d gather round the campfire, drinking cocoa and singing songs. Paul would accompany us on his guitar. To anyone who’s interested, viewers, this was definitely Paul’s first appearance in public as a guitarist.

Paul had just turned fourteen when the happy world we knew came suddenly crashing around us. That normal, quite-average world, steeped in love and affection which Paul and I still look back upon with nostalgia and sadness.

Mum died.

She was only two days in hospital when the end came for her. Once she became ill, Paul and I were sent away to stay with our uncle and auntie. We were still there when we were told that she had died.

I think – indeed I know – that at first we didn’t realize what had happened. I remember that we both felt that the important thing was to show our cousins that we were not softies in any way and to put on what is called “a brave front”. I think we went a bit overboard about this, and that Paul made some flippant remark which sounded pretty callous at the time. Of course, he didn’t mean it. But, as the eldest, he felt he had to say something and what he said was just silly. I know he could have bitten his tongue immediately after.

Paul was far more affected by Mum’s death than any of us imagined. His very character seemed to change and for a while he behaved like a hermit. He wasn’t very nice to live with at this period, I remember. He became completely wrapped up in himself and didn’t seem to care about anything or anybody outside himself.

He seemed

interested only in his guitar, and his music. He would play that guitar in his

bedroom, in the lavatory, even when he was taking a bath. It was never out of

his hands except when he was at school or when he had to do his homework. Even

in school, he and George Harrison used to seize the opportunity every break to

sit and strum.

When we left our auntie’s house and returned home, it was agreed that Dad, Paul and I would take it in turns to do the housework.

“We’re a

family on our own now,” Dad said. “We’ll all have to help.”

But time after time when I came home from school, I would find that Paul hadn’t done his bit. I would go looking for him and sometimes I would find him, up in his bedroom, perhaps, sitting in the dark, just strumming away on his guitar. Nothing, it seemed, mattered to him any more. He seldom went out anywhere – even with girls. He didn’t bother much with any of his friends except his schoolmate George Harrison and John Lennon, who was at the art school next door. Work and work alone – his school books and his guitar – appeared to be the only thing that could help him to forget.

It was a terrible winter the year our Mum died. So bitterly cold. Paul and I would trudge home from school every day, our self-pity increasing the nearer we got to the house. For we knew there’d be no meal ready and no fire lit.

This was after we’d spent some time with our aunts and uncles – we’ll always be grateful to them. Aunt Joan, kindness itself, who knew better, at that time, than to show us any special sort of sympathy. But Uncle Joe was quiet – for him. Uncle Joe’s normally a real knock-out – small in size but big in feelings and with a great sense of humour.

And then a while with Auntie Jin (Jane) and Uncle Harry – they have a large house at Huyton and we went to them for our first Christmas without Mum. Auntie Jin is a small, perceptive woman and very motherly. I remember one day she caught the two of us moping around and looking very much down in the dumps – not a bit like the two happy young chappies we usually were.

She hesitated for a second as though not certain whether she should say anything or not, before she told us: “Listen, loves, I know you’ve gone through a fantastic time and I know the way you’re feeling, but you’ve got to try to think of other people. You’ve got to think of your father. I know this has been a great shock, but we all get great shocks and we have to get over them. Now you’ll really have to pull yourselves together.”

This certainly helped to snap us out of our self-pity for a while, but the effect didn’t last.

Paul, as I’ve told you earlier, went into a deep blue hermit sort of mood which was anything but pleasant for us while it lasted. I used to mope a lot, too, and show in a whole lot of ways that I felt hard done by. Perhaps the most obvious was becoming accident-prone. I was in and out of hospital several times in the next year or so – once with a gashed foot, then with a broken arm, then finally with a few smashed teeth.

Back in our own place, Dad had warned us that we’d have to buckle down and help to do the chores now that Mum was no longer there. But I’m afraid Paul and I left far too much to Dad. As it was, I don’t think we’d have got through if it hadn’t been for our aunties – marvellous, I say again; every single one.

You see, there was also Auntie Mil (left) who took it in turns with Auntie Jin to come over on a Monday and give the house a cleaning and tidying. This meant a long journey for Auntie Mil for she lived across the Mersey, just outside Birkenhead – at least half a hour to get to the ferry, then another hour to get to our place.

We looked forward to these Monday visits for it meant that instead of coming into a cheerless house, there was a fire and what we called a “Mum dinner” – one just like Mum used to make.

Some

Sundays we’d go to yet another auntie’s – Auntie Dil – for dinner. She made

fantastic rich-baked cakes. That helped a lot, for any Sundays spent at home

were a drag. No Mum. It was on Sundays, we missed her terribly.

There were times, of course, when we went back to our old ways – which meant being a couple of daftheads, I suppose. I remember one little difficulty at Auntie Jin’s one weekend. Paul and I found this old paraffin canister and poured a trail of paraffin on the ground and then set a match to it. It went shoooooot! – all lovely like! We thought it was great so we laid a trail across the yard, right up the side of the garage and on to the tarpaulin roof! All we wanted to do was to find if flames would go upwards.

Well, we found out all right! Within seconds Auntie Jin’s garage was burning like a bonfire. Like two little nutters we dashed madly about with buckets, splashing more water on ourselves than on that fire. The garage – maybe the whole house – might have burned down had not a passing policeman seen what was going on and come and helped us put the fire out. We had a right job convincing him we were only trying out a scientific experiment!

But this kind of thing was exceptional at that time. Paul spent most of his time around the house, doing just as much housework as had to and no more and strumming away at his guitar. But at least he made new friends at school and this was important, for it drew him out of himself a bit. It pleased Dad and me for he really way a drag around the house.

One of his new friends was George Harrison, who at this time was a bit of a joke at school because he wore his hair so long. And the more the kids laughed and jeered, the longer George let his hair grow. I think in the end he’d have let it grow below his knees if they hadn’t all got fed up and left off jeering at him.

Paul, of course, also wore his hair long – but it never got as long as George’s. Whenever it got a bit too thick and moppy-looking, Dad ordered: “Off to the hairdresser!” And Paul – whatever his attitude towards officialdom and authority in general – always obeyed Dad’s orders.

***

Paul and

George used to lend each other records and, in general, help each other along.

After school, they’d hold sing-songs together. I couldn’t help but get

interested, too, and at home Paul and I tried harmonising. We weren’t at all

bad. We often sang at family parties, our big number being “We are Siamese, if you please” from Walt Disney’s Lady and the Tramp.

Then I broke my arm and had to go into hospital. Who knows what might have happened if I hadn’t broken that arm? We could have taken “We are Siamese if you please” to the top of the pops and become the Elderly Brothers. But Paul and George had already gone a long way together at that time.

Actually, viewers, I shared the limelight with Paul on what might be described as his first public stage appearance – certainly on any stage outside the school theatre. When I was well enough to leave hospital, Dad brought Paul and me down to a holiday camp at Wales for a break.

Our cousin Mike (Robbins) happened to be producer of the camp talent show and gave us our big chance. Mike thought Paul a rave mimic – although this made him a minority in the family. The rest of them thought that we were simply crackers. I think the only joke they ever laughed at was Paul’s Irish joke.

This is about the two Irishmen who came out of a pub just as an aeroplane was flying past. Mick says: “Begorra, Pat, I’d hate to be up in that plane,” and Pat replies: “Oi, Mick, but I’d hate to be up there without it!” And the only reason they laughed at that was because of Paul’s cod Irish accent. Bet you didn’t know that, brother!

Anyway, cousin Mike had this idea that Paul was really good.

“Why don’t you do your Little Richard piece?” he suggested.

Paul’s face was a book study. “Oo-er,” he said doubtfully. “Do you really think so?”

“You’d be great, real great,” cousin Mike told him.

“I’d be too nervous,” said Paul.

In fact

he was shaking like Patrick Kerr’s left leg when we finally got him as far as

the wings in the theatre. And even then we had to give him a push before we

could get him out on stage. But when he found himself standing in the spotlight

– without quite knowing how he had got there, may I say – he did his little

turn successfully. The applause was just about to die away when the compere

turned the spotlight to where I was standing in the wings and called upon me to

join Paul in a duet.

We must have looked a couple of junior-sized Laurel and Hardys – Paul chubby and all owl-faced, me skinny, pale as powder, and with my arm still in a sling. Anyway we sang “Bye-Bye Love” together and were rewarded with a bar of chocolate each. Talk about the big time!

While I continued breaking things such as my teeth (it was actually Paul’s fault – I was swinging from a door and he was holding on to my legs and I shouted “Let go!” and he didn’t), he was busy catching things. Such as a mysterious disease which produced funny little pink spots all over him. The doctor at the scout camp where this happened scratched his head and said he didn’t know what it was. At the hospital the doctors recommended lotions and various medicines for Spotty McCartney, they also scratched their heads and said they didn’t know what it was either. Then one day those funny little spots simply vanished by themselves! Nobody has ever found out why they came – or why they went away!

John Lennon’s arrival on the scene changed everything for Paul and George. He was very much the dominant personality in those early days. And as you all know, viewers, even today he has a mind of his own, thank goodness. He was a fairly wild kid, then – a bit cheeky and a bit mixed up. He had, in fact, had a very unsettled childhood, and somehow he had developed a rather strong, individual, dissenting personality. He was a pupil at the Quarry Bank High School and when he, Paul, George, Len, Ivan, Pete and Griff formed a skiffle group, they naturally called it The Quarrymen.

At first, to be very frank, Dad didn’t like John Lennon. John had very little respect for his elders in those days and he dressed a bit like a Ted. In fact, he was an early existentialist. Today, now that Dad understands John and knows what makes him tick, and vice-versa, they get along together like a house on fire.

Paul and I had begun to drift apart at this time. Paul was entering a new world with new and exciting friends. Of course, we still got on very well together – and still shared the same sense of humour. At the table we’d have laughing spasms that would make Dad mad. “What are you laughing at?” he’d demand, a bit puzzled. And, of course, this would only make us laugh all the more at our own joke – whatever it happened to be that day. We’d both roll under the table convulsed and Dad would shout: “Daftheads!” and then get up and walk away in disgust. Poor Dad! I think that he suspected our sanity at times!

You couldn’t really blame him. He had his standards and he and Mum had brought us up fairly strictly. He certainly didn’t want us turning into tearaways. And the way John dressed – with long sideburns, drainpipe trousers and all – didn’t appeal to him much. Once, when he sent Paul out to buy himself a new pair of trousers, he warned him: “None of those drainpipes, mind!” Paul was nothing if not crafty, though. He brought home a normal pair, showed them to Dad for his approval, then went back and got them altered into drainies! The funny thing is that, because of all the things happening to us two now, Dad seems to be getting younger every day. Nowadays he wouldn’t dream of buying anything but narrow trousers for himself.

Except for his school-work, Paul had become entirely wrapped up in his music. He’d never go to a dance – unless he had been asked to play at it. Not that he dances very well, anyhow – he just walks around the room on his elbows and knees. Girls meant very little to him then. If a girl was prepared to talk about music or about art, all right! If she wasn’t – then he had little time for her.

But he was never bad-mannered to any girl. He would never do anything that Mum and Dad would be ashamed of. If he took a girl out, he took care to create a good impression. If she invited him home, he would be polite and respectful to her parents; none of this cheeking up the older generation. Quite a few girls fancied him as “a steady.” But he was too much concerned with The Quarrymen and their career to bother very much. It had never occurred to me that he could be so single-minded about anything. It was a big surprise. Our kid dedicated and all that!

Next step

was the Beatles, of course. When skiffle began fading, John, Paul and George

decided it was time to bury the Quarrymen and try something new – and

particularly with a new name. They were experimenting with a new kind of music

– a mixture of rhythm and blues – picked up from discs made by little-known (to

them!) artists such as Bo Diddley, Chuck Berry and Ray Charles. Then one

evening they all went up to Paul’s room (where they often practised) and took

an encyclopaedia with them. They wanted a new name which would suit these new

sounds they were making. They got as far as “I” for Insects in the book without

finding anything that struck a chord, and at this spot I remember Paul saying

impatiently: “Aw, there won’t be anything there.”

For a laugh, however John suggested: “What about Beetles?” The name didn’t even register. They didn’t even take it seriously when John added: “Beetles with an A – Beatles!” They thought he was only kidding.

They finished going through the book but couldn’t find anything and finally somebody said: “Well, Beatles made us laugh, didn’t it?”

“But it’s a bit off-putting, isn’t it?” said somebody else.

“Then let’s make it The Silver Beatles?” suggested John.

“Aw roight, then or what!” said Paul, jocularly.

So for a while they called themselves The Silver Beatles until they discovered that nobody would go to the trouble of pronouncing such a mouthful! Then they quietly dropped the “silver” bit – and made themselves a lot of gold! (Ho! Ho!).

When Dad and Paul saw how keen I was to learn the drums, they bought me a set. Unfortunately, a little while before, I’d broken my wrist. The bones had reset all right but a single nerve hadn’t healed properly and the result was that I could only play the drums really well with one hand.

Even so, despite my bad wrist, I might have been with them today – imagine that, Mike RingoStarClub! – if it hadn’t been for my brother. Paul is so gifted that he really could play any instrument he wanted to, if he set his mind to it. Anyhow, one day when I got up from the drums, he sat down in my place and began idly tapping on them – just to pass the time, really. But then, as he warmed up, he let himself go! It was real virtuoso stuff compared with my feeble efforts and I listened to him play in a sort of daze.

I didn’t hesitate – I decided then and there to give up the drums. If Paul could play like that without any real practice – then what hope was there for me after all the work I’d put in on them? I realized that I’d simply never be good enough. So I quit – just like that! That’s one way of passing up a fortune!

The biggest day in Paul’s life, before fame and fortune eventually overwhelmed the Beatles, was when the group got an offer to play in Hamburg. Paul hopped up and down with excitement when he broke the news to me as we rode home together on the bus one evening. His only worry was that Dad wouldn’t allow him to go to Germany. And, indeed, at first Dad wouldn’t allow him. But when he saw how depressed this made Paul, he soon gave in.

That five-week season in the nightclub-quarter of Hamburg almost finished the Beatles before they had really started! They were worked practically to death. Their hours were little short of suicide – from 10 p.m. till midnight and from 2 a.m. till 5 a.m. Fantastic hours for kids who were little more than schoolboys. And even then they had to buy their own food – which didn’t leave very much over for expensive guitars or clothes or other things. When Paul returned home and rang the front doorbell, Dad and I hardly recognized him. His hair was really wild and he was so thin that he looked like a refugee from a concentration camp. I couldn’t call him “Fatty” any more, and even though we did fatten him up a bit again, he was never so chubby.

Most people have the idea that the Beatles were an overnight sensation. That’s not true. Even when they were playing in the Casbah and the Cavern and other beat clubs in Liverpool, they never earned enough money to keep themselves. In fact, Dad got so fed up that one day he said to Paul: “I’ve had just about enough of this, son. You’ve got to find yourself a job.”

The Labour Exchange, Renshaw Hall, Renshaw Street. (LRO)

So, Paul tried the Labour Exchange and they found him a job as an apprentice to an electrical firm. It didn’t turn out to be much of a job – all Paul had to do was to sit around all day coiling bits of wire. He hated it, and every lunchtime he would slip away to the Cavern where he joined John and George and played alongside them. Gradually these lunchtime sessions stretched longer and longer until one day he was seen sneaking back to work, late for the umpteenth time, and got the sack.

Next he found a job humping tea-chests in a loading bay – not much of a job for somebody with five “O” levels and an “A” level. Things were pretty hard all round for all the Beatles at this time – John Lennon, for instance, was out navvying on the roads and George was an electrician in a big department store. Even though they still met regularly at the Cavern for their famous lunchtime sessions, they would almost certainly have remained just where they were if Brian Epstein hadn’t come along. He pulled them together, made them cut out their slack, easy-going ways, introduced a fairly severe discipline and gradually worked them into the tremendously professional slack-easy-going outfit they are today.

He didn’t accomplish any of this without a great deal of hard work. Few people know just how near Paul, for example, came to wrecking the Beatles early on. To say that they were all very slack is, in fact, a sort of major understatement – they were nutty slack. Paul has always been the world’s worst timekeeper. It’s almost impossible to get him up in the mornings, for instance. And you ought to see him when he starts shaving. He dithers about for hours before beginning, and then, when he starts, it’s as though he were performing a major operation.

In Liverpool, I should explain, the groups would play several engagements at several different clubs and dance halls during an evening. As the Beatles got slacker and slacker, they kept turning up later and later at the clubs. Once or twice they turned up so late that they missed their “spot” altogether. Unhappily, a great deal of this was Paul’s fault. Though to be fair, he wasn’t always to blame. Brian stood for this for a while, then he gave the entire group an ultimatum. “Either you change your attitude – or we split!” The Beatles didn’t need to think about it; by this time they realized they needed each other.

Well, the

rest of the Beatles’ story is fairly familiar and the only question now is where

are they all going? And in particular, where is Paul going?

Today Paul’s big interest is in creating his own tunes.

He began writing them in a very simple way – just twanging chord sequences on his guitar. Then he and John began working out an understanding together – although they haven’t any special method. One of them thinks up a theme, jots it down, and then they work on it together, polishing it into its final shape.

As a group, the Beatles have one big ambition – to stay on top. It’s really more pride than ambition.

They want to go on making films – although they don’t really fancy themselves much as actors. At the premiere of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ you should have seen how they squirmed with embarrassment at certain scenes. But now, with the help of director Dick Lester, they have improved tremendously and their new film ‘Help!’ in my humble opinion, is going to be a fantastic hit.

That premiere of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’ was a great occasion for the McCartney family. Paul had sent for all our aunties and they turned up in a fleet of cars at a West End hotel for the reception.

Paul presented Dad with a horse that night – for his birthday. He went up to Dad during the reception and handed him this painting of a horse. “Here you are, Dad. Got this for your birthday.”

Dad looked at the painting and said: “Lovely, son, that’s for my birthday, is it?” He thought we were playing one of our daft jokes on him.

He didn’t realize that Paul had bought him a real horse and that this was just a painting of it! You ought to have seen his face when everything finally clicked. I’ve never seen him look so pleased. Or so proud.

When

people find I’m Paul’s brother, they sometimes ask what his views on love and

marriage are and what the real truth is about his romances.

Well, let’s put it this way. I can’t envisage him getting married for quite a while yet although Paul’s the kind who just might decide to get married suddenly.

He likes to talk about marriage – and particularly its problems, to John and Cythnia Lennon, as we call her. By now, at least, he knows all the snags – and all the advantages.

What about his much-publicized romance with Jane Asher, then, viewers? Last year it was hinted in the press that their holiday in the West Indies was really a honeymoon. Those reports, I can tell you, were pure nonsense. But it’s a fact he’s very fond of Jane who first got to know him when he was a comparative nobody – a hopeful bloke in a maybe-up-and-coming group called the Beatles. At that time she was a fairly big name in theatrical and pop circles through her appearances in Juke Box Jury and other TV programmes. She and Paul have known each other for about two years now and have knocked about on-and-off during part of that time.

They genuinely like each other and our families are very good friends. But that’s as far as it goes.

What kind of a girl is he looking for? That’s a tough one. She would have to be good-looking. And intelligent. That goes without saying.

He certainly likes girls who have artistic interests. For a while he went around with an art student called Celia. But she couldn’t stand the pace of being his girl friend and gave him up. Before that he met another artistic type, Carol. She made a nice change from the type of girl he was mostly meeting then. They usually only wanted to talk about discs and the Top Ten.

What do you think a Beatle does when he takes a girl out? Lives it up? Wines and dines? Dances? Tours the night spots? I don’t say Paul doesn’t enjoy going out on the town now and then. But when he took Carol out, they both jumped on a bus and went to see an art exhibition! I know he was very impressed by her: she knew a great deal about paintings and artists in general and could talk very intelligently and sensibly about the subject. I think you can be sure that when Paul gets married, it won’t be to just a pretty face.

Has success spoiled our kid? Is he a big-head now? Don’t ask me, I never see him! Seriously, the real truth is that success has actually improved him a lot. He’s a very much nicer person now than he was just after Mum died, for instance. He was hard to live with in those days. He was wrapped up in himself – and apparently he didn’t want people breaking in on his life.

Today, he’s just the reverse – and I really do mean that. He considers other people now and takes into account people’s feelings. He’s always polite to everyone – waiters, taxi-drivers, agents.

How would I sum him up then? BUSY! No – seriously again – I think I’d say he’s a bloke who has been able to take success well. Far from doing him harm, it has made him a very sympathetic character. Having achieved fame and made a lot of money, I think that the real Paul McCartney has just emerged.

That means a generous, humorous young man, far more intelligent and far more sensitive that most older people would believe. A young man with considerable artistic gifts and interests – and decidedly a dedicated musician.

On the whole, a very reasonable human being. In fact, fantastic – like Dad and me.

Mike McCartney

Notes

* In 'Thank U Very Much' he referred to it as Chinese Farm. Having spoken to other Speke residents from that time only a few recognised this nickname and those who did all agreed it was Chinese Farm. When I finally worked out where it was, and what it was actually called, I mentioned it to Mike. He said he never knew it as that, only as Chinese Farm, and he had no idea where this nickname had come from. Paul mentions Chinese Farm in his unreleased song 'In Liverpool' available on YouTube.

** "There were ponds with sticklebacks in. Now there's a sodding great Ford factory there that goes on for acres and acres." (George Harrison, Anthology)

Magazine pages from tracks.co.uk – An original issue of Woman magazine dated 21st August 1965. It contains a 4-page article regarding Paul McCartney by his brother Mike along with various other articles and advertisements. The magazine measures 26cm x 34.5cm (10.2 inches x 13.5 inches).

Superb! I love Mikes stories!

ReplyDeleteThanks. Glad you enjoyed it.

ReplyDeleteThanks for these stories i really enjoyed reading them, some of them very funny some sad ones but overall fantastic.

ReplyDelete