12

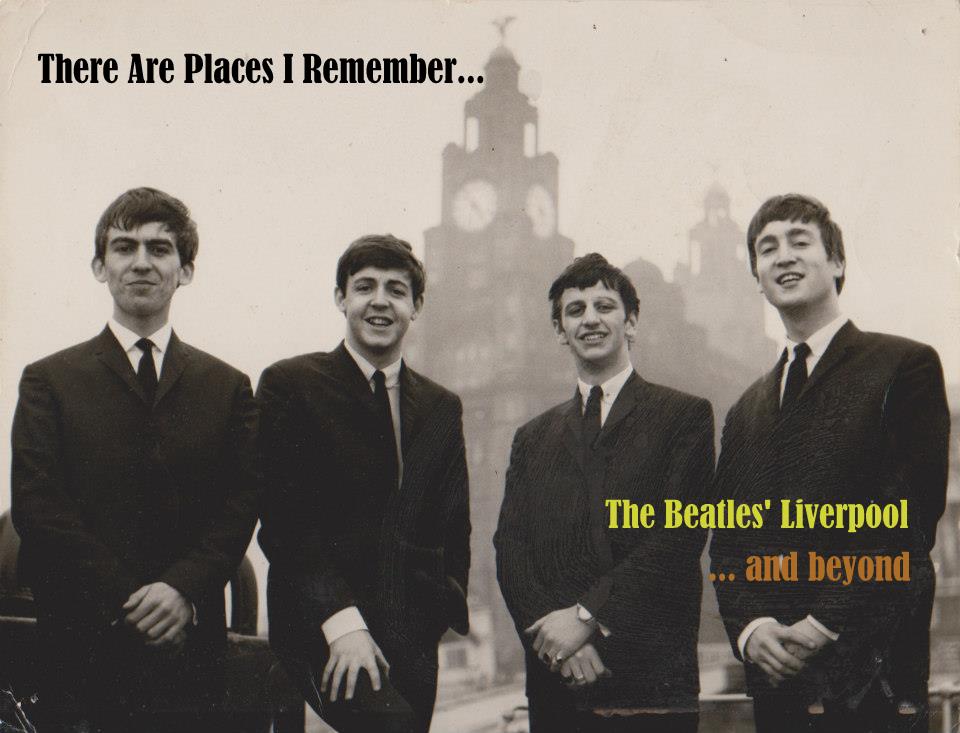

Arnold Grove

The

birthplace and home of George Harrison.

12

Arnold Grove

Wavertree

Liverpool,

L15 8HP

The

birthplace and home of George Harrison.

I was born in 12 Arnold Grove, Liverpool, in

February 1943. My dad had been a seaman, but by then he was driving a bus. My

mother was from an Irish family called French, and she had lots of brothers and

sisters. My mother was Catholic. My father wasn't and, although they always say

people who weren't Catholics were Church of England, he didn't appear to be

anything. (George

Harrison)

In

later years Harry and Louise always said they married in 1930. They didn’t. The

Catholic Louise French was actually six months pregnant when she married

Protestant Harry Harrison on 20 May 1931 at the Liverpool registry office on High

Park Street, Dingle. The Priest at her local church, Our Lady of Good Help had offered none, refusing to marry a 20 year

old girl who was pregnant by a ‘Proddy Dog’.

47 Cecil Street with the black door

(right)

They

were still living here when their first child, also named Louise was born on 16

August 1931. As was the custom the Priest from Our Lady of Good Help visited

them but instead of offering her and the baby kind words he denounced Louise

and declared the new baby a ‘b*stard’ in the eyes of God. Harry threw him out

of the house. To make matters worse, whilst Harry was back at sea the

interfering Jane took baby Louise and had her christened in the Protestant

church. To say there was some friction between the two Mrs Harrisons is

probably an understatement.

Harry

and Louise had put their names down for a Liverpool Corporation House but it

would be years before they got one. With things becoming intolerable in Cecil

Street they moved into rented accommodation at 12 Arnold Grove, a two up – two

down terraced house in the next street to Albert Grove where Louise’s family

still lived. This was ideal for Louise. With Harry away at sea she now had her

own family close by to help her with the new baby. Albert Grove and Arnold

Grove shared the same private landlord, Mr Miller who would visit every week to

collect his ten shillings rent (about £22 today). Miller had probably told Louise’s

parents about the vacancy in Arnold Grove.

Albert

Grove was named after Queen Victoria’s husband - Albert Grove - whereas Arnold

was named after the Queen’s dresser, Frieda Arnold. Both streets were

unadopted, meaning the residents had to make their own arrangements for waste

disposal and maintenance rather than have the service provided by the local

authority.

Number

12 was (and even now, after all these years, still is) very small, yet Harold

and Louise would end up living there with their four children until 1950.

Despite

its size, the house quickly accumulated items that Harry had collected on his

overseas voyages. Pride of place in the front room, which the Harrisons kept

‘for best’ was a leather three piece suite (sofa) which Harry had arranged to

have shipped back from America. A leather sofa was unheard of in Wavertree in

those days and yet the Harrisons barely used it. The family lived in the back

room, the kitchen with its red and blue floor tiles and a fire in the grate.

Louise

gave birth to a second child, a son on 20 July 1934. The tradition of naming

the child after the parent continued as Harry, Louise and Louise welcomed

Harold James Harrison into the world.

On 5

August 1934 Louise and Harry held a double baptism at Our Lady of Good Help for

baby Harold and Louise who was nearly three years old. I wonder what persuaded

the priest to change his mind?

There

are conflicting stories about what caused Harry to leave the merchant navy. The

romantic version is that he wanted to spend more time with his new family and

less at sea. The other says that John French - Louise’s father – was unhappy

with how much time Harry was away from home leaving Louise to bring up the two

children on her own, and eventually wore him down, persuading him to take a job

on land. Harry decided to leave the White Star line and his life on the ocean

once they had enough money saved to tide them over.

Harry

finally left in 1936 when Britain was in the middle of the Great Depression.

Although Harry had some savings behind him there was no work ahead, and with no

qualifications he spent the next two years struggling to find a job. He

received ‘dole’ money, 23 shillings (about £40 now) a week employment benefits

for perhaps for the full twelve months he was entitled to it.

In 1937

Harry finally found a job with prospects, a bus conductor for the Liverpool

Corporation Passenger Trust (the LCPT) for which he received £2 per week (about

£70 today). When he discovered that the drivers earned more he began taking

lessons. By 1939 he was behind the wheel of a Corporation bus on the south end

route travelling from the city centre out to Garston and the new Speke estate.

And

then the Second World War started.

There

was an unexpected addition to the Harrison family on 20 July 1940 when Louise

gave birth to another son, Peter Henry Harrison, exactly six years to the day

after the birth of her first. He was a huge baby, weighing nearly 12 pounds at

birth, but a sickly one. According to his sister, Peter was the first baby in

England to survive an operation to correct his intestines which had extended

into the umbilical cord.

Louise

was not present at her brother’s birth. She was in a convalescent home

recovering from an illness and would later recall suffering cruelties and

indignities from nursing staff. She returned home when he was a month old in

August, 1940 just in time for his christening at Our Lady of Good Help on 13

August and her 9th birthday.

The

following week the first bombs of the Blitz fell on Wavertree.

On 4

September the goods station at Edge Hill at the top of Wavertree Road was

bombed but emerged unscathed. Eight days later bombs fell on Wellington Road,

demolishing houses in the street where Harry had lived as a child. Further

bombs fell on Wavertree Road on 7 October. This is probably the raid Aunt Mimi

would later recall as taking place the night John Lennon was born – there was

no actual raid on the ninth.

Wavertree

was now a clear target for the Nazis and the Harrison’s were not alone in

thinking each night could be their last. Wavertree Playground, known locally as

“The Mystery” and a favourite place for the locals to take their children was

bombed on the night of 4 November. Adjacent houses were damaged and a gas main

was fractured and caught fire only to be extinguished by a water main which

fortuitously burst nearby. The Germans had another go at the Edge Hill goods

depot on 12 November but missed. Stray oil incendiary bombs instead hit the

roof of the post office on Wavertree Road.

A map

showing the Edge Hill end of Wavertree - a major target for the Luftwaffe.

Several Beatles - related sites are visible including Bridge Road (former site

of Massey and Coggins), Cecil Street, Ash Grove (where both George's dad and my

own lived as children) and the LCPT social club where Harold Harrison arranged

a gig for the Quarry Men. Click to enlarge.

On the

evening of Thursday 28 November 1940 Rachael Lucas, known to all as ‘Nancy’ was

at home with her mother, Mabel Ashcroft, in Ashfield, a row of terraced housing

four streets away from Cecil Street, and five away from the Gas Works which

marked the end of Wavertree and the beginning of Edge Hill. Running down the

other side of the gas towers was Spofforth Road and it’s artery, Bridge Street

(where Paul McCartney would later work for Massey and Coggins) and beyond them

the huge railway sidings. Rachael worked as a post-girl delivering mail from

the Wavertree post office by bicycle. She’d once knocked a policeman over

during a blackout. On another occasion she was out during daylight with her

friend when a plane flew low over their heads. They both cheered and waved at

the pilot until somebody shouted ‘get down you bloody fools’, just as a second

plane came into view hot on the tail of the first. The second plane was an RAF

Spitfire or Hurricane. The first plane was German!

As soon

as the sirens sounded Rachael and her mother joined families all over Wavertree

and ran for the nearest cover, the communal air-raid shelter in the street or

the ‘Anderson’ shelter in the back garden, if they were lucky enough to have

one. Some preferred to hide under their own stairs, supposedly the strongest

point in the house. At the other end of Wavertree the Harrisons huddled with

their neighbours in the brick shelter built in the middle of Arnold Grove and

hoped for the best.

This

was a major attack by 324 aircraft. In the initial raid, Heinkel He 111s

dropped 30,960 incendiary bombs. As Thursday became Friday, Dornier DO 17 and

Junkers JU-88s dropped a mixed load over Wavertree comprising 356 tons of High

Explosives (including 151 ½ ton bombs), Flambo and 30 one- ton parachute sea

mines (of which 8 failed to explode).

This

was the night when the Junior Instruction Centre on Durning Road was hit by a

mine. The building collapsed and of the 300 people taking cover in the basement

shelter 164 were killed. Today it is remembered as the worst single loss of

life from bombing during 1940-41 in the UK.

The Gas

Works on Spofforth Road (above) and the Railway yard were prime targets for the

Luftwaffe but it was the houses within a square mile of the Wavertree Road area

that bore the brunt of the attack. By the end of the raid 2000 people were

homeless and the Gas Works were burning.

I

certainly remember the night the gas works went up. Imagine it was on Alfred

Street but I am not too good at remembering all the street names now. I lived

on Spekeland Vale, and remember the night and the next couple of days –

tremendous damage to the surrounding area of the gas works (Nita Jones,

Rootsweb)

The

street was Spofforth Road that took a pounding, it had the Co-op livery

stables, I think that the horses were untouched. We lived on Cambridge street

and took the blast which blew in the parlour window, the frame, the whole

works. I believe a navy bomb disposal man got awarded the highest possible

medal for his courage. Nights to remember, we spent a lot of time in the

community underground air raid shelter in Piggy Much Square. (Hugh Jones,

Rootsweb)

Sixteen

people lost their lives in Ashfield that night.

Rachael

and her mother survived the raid. Their home did not. The blast had blown the

front of the house out. Amazingly, standing in the street untouched amongst the

rubble was their upright piano. It didn’t have a mark on it.

Rachael

Lucas was my maternal Nan. When I was a child I’d ask her to tell me the story

about the piano that survived the bombing over and over again. She’d always

remind me “They were going for the gas works but missed and got us”.

A few

years ago I found this photograph of a piano in a bombed out street in

Liverpool. I couldn't believe it. Was this my Nan's piano? With further

research I established that the photo was taken in Bootle but the similarities

are plain to see.

Because

it was further away from the Gas works 12 Arnold Grove had fared better.

Emerging from the shelter the Harrisons were relieved to find their house was

still standing. It was not completely unscathed. The shockwaves from a huge sea

mine had blown all the windows in and the shards of glass had lacerated the

American leather sofa. Louise Harrison would later recall her mother joking ‘If

I’d known that was going to happen we could have been sitting on it all these

years!’

One of

the parachute sea-mines that miraculously failed to explode. Score Lane,

Childwall, about 1.5 miles from Arnold Grove.

The

last bombs to fall on Liverpool did so in January 1942 so I was surprised to

learn that the two oldest Harrison children were evacuated so late in the Blitz.

It seems that between 1942-43 Louise, then 10 and Harry,7 were sent to Wales,

staying with different families. Harry reportedly enjoyed his stay with a

family who had two teenage sons while his sister stayed with a childless

couple.

Around

May 1942 Louise found that she was pregnant again and this time it was planned.

With her oldest two children of a similar age it’s said that Louise wanted a

playmate for Peter.

Call

the midwife!

On

Thursday 25 February 1943 George Harrison was born in the front upstairs

bedroom of 12 Arnold Grove at ten minutes past midnight, entering a world he

later described as “deep in the Second World War, deep in Liverpool, and deep

in winter”. He was overdue and weighed a massive 10 ½ pounds with eyelashes,

long hair, full finger nails and brown hair.

In

those days Dads were not permitted in the room during the birth. The midwife

informed Harry he had a new son and he would later remember tiptoeing up the

stairs to meet him. He was shocked by what he found, “a miniature version of

me’’. He couldn’t believe how alike they looked.

The

next day Harry went to register the birth at Wavertree Town Hall without first

consulting Louise about a name for the new baby. Walking the short distance

along the High Street he decided on George and later reasoned if (the name) was

good enough for the King it should be good enough for him.

He was

baptised as Georgius Harrison on 14 March 1943 at Our Lady of Good Help. His

sister Louise and his aunt Mary (Fox, formerly French) were godmothers but for

some reason there was no godfather.

I had

two brothers and one sister. My sister was twelve when I was born; she'd just

taken her Eleven Plus. I don't really remember much of her from my childhood

because she left home when she was about seventeen. She went to teacher

training college and didn't come back after that.

My

grandmother - my mother's mother - used to live in Albert Grove, next to Arnold

Grove; so when I was small I could go out of our back door and around the back

entries (they called them 'jiggers' in Liverpool) to her house. I would be there

when my mother and father were at work.

Arnold

Grove was a bit like ‘Coronation Street’, though I don't remember any of the

neighbours now. It was behind the Lamb Hotel in Wavertree. There was a big

art-deco cinema there called the Abbey, and the Picton clock tower. Down a

little cobbled lane was the slaughterhouse, where they used to shoot horses.

My

earliest recollection is of sitting on a pot at the top of the stairs, having a

poop - shouting, 'Finished!' Another very early memory is as a baby, of a party

in the street. There were air-raid shelters and people were sitting around

tables and benches. I must have been no more than two. We used to have a

photograph of me there, so it's probably only because I could relive the scene

when I was younger, through the photograph, that I remember it.

VE Day

Party 8 May 1945 - from right Harry, Peter, Louise, and George aged 2. Note the

brick air-raid shelter behind Harry.

Our

house was very small. No garden. Two up and two down - step straight in off the

pavement, step right out of the back room.

Each

room downstairs was about ten feet square (very small) and yet despite the lack

of space the front room was never used. It had the posh lino and a three-piece

suite, was freezing cold and nobody ever went in it. We'd all be huddled

together in the kitchen, where the fire was, with the kettle on, and a little

iron cooking stove.

Like

many home of the time, there was no central heating, no bathroom and no indoor

toilet. The winters could be freezing. George later remembered that in the

winter there used to be ice on the windows and in fact you would have to put a

hot water bottle in the bed (keep nipping upstairs to keep it moving) then whip

your clothes off and leap in. And then oooooooooooohhh, lie still and then by

next morning you'd just got warm and then you'd wake up, "come on, time

for school", put your hand out of the bed. Freezing. Oh dear.

Harrison

recalled that he and his brothers dreaded getting up in the morning because it

was literally freezing cold and they had to use the outside toilet.

The

four children shared the back bedroom. In his infancy George had slept in his

parents room but he later moved in with his siblings, Louise in one bed, Harry

and Peter in another and George in a cot.

A later

resident of Arnold Grove was Anthony Hogan, author of From a Storm to a

Hurricane, the biography of Rory Storm and the Hurricanes. I asked him to

describe the layout of the house: The front door goes straight into the living

room which would have been about 12 foot square (I’m guessing here). At the

back was a small kitchen. The stairs are at the back of house. They go up from

the kitchen towards the front door if you get what I mean. Upstairs is a tiny

landing 2 foot x 2 foot. The front bedroom was the largest, and ran the length

of house across. The back bedroom runs towards back of house and is smaller.

(Anthony’s son) had a single bed, wardrobe, chest of drawers etc. There was not

much room with that in there, so imagine it with all those kids in there. The

houses were extended when we lived there. It was all knocked through so it had

space. Loved it there, the fans were funny at times. We needed a larger house.

Liked it there though.

A lot

of the garden was paved over (except one bit where there was a one-foot-wide

flowerbed), with a toilet at the back and, for a period of time, a little

hen-house where we kept cockerels.

Peter and George in the backyard at No. 12

Peter and George in the backyard at No. 12

There

was a zinc bathtub hanging on the backyard wall which we'd bring in and fill

with hot water from pans and boiling kettles. That would be how we had a bath.

We didn't have a bathroom: no Jacuzzis. Good place to wash your hair,

Liverpool. Nice soft water.

I had a

happy childhood, with lots of relatives around - relatives and absolutes. I was

always waking up in the night, coming out of the bedroom, looking down the

stairs and seeing lots of people having a party. It was probably only my

parents and an uncle or two (I had quite a few uncles with bald heads; they'd

say they got them by using them to knock pub doors open), but it always seemed

that they were partying without telling me.

I don't

remember too much about the music, I don't know whether they had (anyone

performing) music at the parties at all. There was probably a radio on.

There

was always music in the house, some of it quite unusual for the times. Louise

enjoyed listening to Indian classical music on ‘For the Indian Forces’ every

Sunday morning on BBC radio. It’s tempting to think her unborn fourth baby was

absorbing all this from the womb.

My

eldest brother, Harry, had a little portable record-player that played 45s and

33s. It could play a stack of ten records, though he only owned three. He kept

them neatly in their sleeves; one of them was by Glenn Miller. When he was out

everything was always left tidy; the wires, the lead and plugs were all wrapped

around, and nobody was supposed to use it. But as soon as he'd go out my brother

Pete and I would put them on.

We'd

play anything. My dad had bought a wind-up gramophone in New York when he was a

seaman and had brought it back on the ship. It was a wooden one, where you

opened the doors; the top doors had a speaker behind and the records were

stored in the bottom. And there were the needles in little tin boxes.

He'd

also brought some records from America, including one by Jimmie Rodgers, 'the

Singing Brakeman'. He was hank Williams's favourite singer and the first

country singer that I ever heard. He had a lot of tunes such as 'Waiting For A

Train', and 'Blue For A Train' and that led me to the guitar.

Harold

Harrison with his four children.

In the

late 1970s George took (his second wife) Olivia to see the house. No one was in

so they sat outside in the car and tried to imagine what it was like inside.

George suspected the new owners had at some point knocked the fireplace out,

installed “one of those little tiled jobs” and probably now had running hot

water.

I had

wondered whether George only went back the once. Did he ever take his son Dhani

to have a look? Did the new owner ever let him in?

Anthony

Hogan was able to confirm that George did make a return visit: Did you know

George once turned up at the house with his wife. (The lady living in number

12) Kath told us she answered a knock and he was standing there. He said he had

once lived there and asked if he could come in to look. He had a cuppa with

Kath.

(Somebody)

put a plaque up once without telling her. She came home and found it on her

house. She was so upset by it. I removed it for her. I should have kept it as

it would be worth a bit now.

Certainly

the current owners appear to want no part of the Beatles industry and this is

something one should bear in mind visiting any of the Beatles' former homes –

for the most part they are still occupied by ordinary people and their privacy

should be respected. I’ve stood at the corner of Admiral Grove and witnessed a

group of tourists peering through the window and leaning against the front door

of number 12 to pose for photographs. I think I’d get fed up with that every

day…..

George’s

brother Harry would later recall: Our little house was just two rooms up and

two rooms down, but, except for a short period when our father was away at sea,

we always knew the comfort and security of a very close-knit home life.

George

had similar fond memories of Arnold Grove:

It was OK that house, very pleasant being little and it was always sunny

in the summer. But then we moved, after about 25 years on the housing list, we

moved.

It was

actually nearer eighteen years since Harry and Louise had applied for a council

house. At the time of their original application they had one child, Louise,

who had since grown up and moved on. Now they had three more – Harry, fifteen,

Peter, nine and six years old George. On 1 January 1950 the Harrisons left

Wavertree and moved to a newly built home at 25 Upton Green in Speke.

Unfortunately they quickly wanted to move back. George: As soon as we got to

Speke we realised we had to get out of there, fast...the place was full of fear

and people smashing things up.

The

Harrisons got on another list.

Source:

The

George Harrison quotes are taken from his biography, ‘I Me Mine’ and interviews

given for ‘The Beatles Anthology’. The Books “Thats The Way God Planned It” by

Kevin Roach, and “Tune In” by Mark Lewisohn were also of assistance.

Thanks

to Anthony Hogan for his personal memories.

I hope you enjoyed the

Rutles' joke ;)

I was born in 12 Arnold Grove, Liverpool, in

February 1943. My dad had been a seaman, but by then he was driving a bus. My

mother was from an Irish family called French, and she had lots of brothers and

sisters. My mother was Catholic. My father wasn't and, although they always say

people who weren't Catholics were Church of England, he didn't appear to be

anything. (George

Harrison)

In

later years Harry and Louise always said they married in 1930. They didn’t. The

Catholic Louise French was actually six months pregnant when she married

Protestant Harry Harrison on 20 May 1931 at the Liverpool registry office on High

Park Street, Dingle. The Priest at her local church, Our Lady of Good Help had offered none, refusing to marry a 20 year

old girl who was pregnant by a ‘Proddy Dog’.

47 Cecil Street with the black door

(right)

They

were still living here when their first child, also named Louise was born on 16

August 1931. As was the custom the Priest from Our Lady of Good Help visited

them but instead of offering her and the baby kind words he denounced Louise

and declared the new baby a ‘b*stard’ in the eyes of God. Harry threw him out

of the house. To make matters worse, whilst Harry was back at sea the

interfering Jane took baby Louise and had her christened in the Protestant

church. To say there was some friction between the two Mrs Harrisons is

probably an understatement.

Harry

and Louise had put their names down for a Liverpool Corporation House but it

would be years before they got one. With things becoming intolerable in Cecil

Street they moved into rented accommodation at 12 Arnold Grove, a two up – two

down terraced house in the next street to Albert Grove where Louise’s family

still lived. This was ideal for Louise. With Harry away at sea she now had her

own family close by to help her with the new baby. Albert Grove and Arnold

Grove shared the same private landlord, Mr Miller who would visit every week to

collect his ten shillings rent (about £22 today). Miller had probably told Louise’s

parents about the vacancy in Arnold Grove.

Albert Grove was named after Queen Victoria’s husband - Albert Grove - whereas Arnold was named after the Queen’s dresser, Frieda Arnold. Both streets were unadopted, meaning the residents had to make their own arrangements for waste disposal and maintenance rather than have the service provided by the local authority.

Number

12 was (and even now, after all these years, still is) very small, yet Harold

and Louise would end up living there with their four children until 1950.

Despite

its size, the house quickly accumulated items that Harry had collected on his

overseas voyages. Pride of place in the front room, which the Harrisons kept

‘for best’ was a leather three piece suite (sofa) which Harry had arranged to

have shipped back from America. A leather sofa was unheard of in Wavertree in

those days and yet the Harrisons barely used it. The family lived in the back

room, the kitchen with its red and blue floor tiles and a fire in the grate.

Louise

gave birth to a second child, a son on 20 July 1934. The tradition of naming

the child after the parent continued as Harry, Louise and Louise welcomed

Harold James Harrison into the world.

On 5

August 1934 Louise and Harry held a double baptism at Our Lady of Good Help for

baby Harold and Louise who was nearly three years old. I wonder what persuaded

the priest to change his mind?

There

are conflicting stories about what caused Harry to leave the merchant navy. The

romantic version is that he wanted to spend more time with his new family and

less at sea. The other says that John French - Louise’s father – was unhappy

with how much time Harry was away from home leaving Louise to bring up the two

children on her own, and eventually wore him down, persuading him to take a job

on land. Harry decided to leave the White Star line and his life on the ocean

once they had enough money saved to tide them over.

Harry

finally left in 1936 when Britain was in the middle of the Great Depression.

Although Harry had some savings behind him there was no work ahead, and with no

qualifications he spent the next two years struggling to find a job. He

received ‘dole’ money, 23 shillings (about £40 now) a week employment benefits

for perhaps for the full twelve months he was entitled to it.

In 1937

Harry finally found a job with prospects, a bus conductor for the Liverpool

Corporation Passenger Trust (the LCPT) for which he received £2 per week (about

£70 today). When he discovered that the drivers earned more he began taking

lessons. By 1939 he was behind the wheel of a Corporation bus on the south end

route travelling from the city centre out to Garston and the new Speke estate.

And

then the Second World War started.

There

was an unexpected addition to the Harrison family on 20 July 1940 when Louise

gave birth to another son, Peter Henry Harrison, exactly six years to the day

after the birth of her first. He was a huge baby, weighing nearly 12 pounds at

birth, but a sickly one. According to his sister, Peter was the first baby in

England to survive an operation to correct his intestines which had extended

into the umbilical cord.

Louise

was not present at her brother’s birth. She was in a convalescent home

recovering from an illness and would later recall suffering cruelties and

indignities from nursing staff. She returned home when he was a month old in

August, 1940 just in time for his christening at Our Lady of Good Help on 13

August and her 9th birthday.

The

following week the first bombs of the Blitz fell on Wavertree.

On 4

September the goods station at Edge Hill at the top of Wavertree Road was

bombed but emerged unscathed. Eight days later bombs fell on Wellington Road,

demolishing houses in the street where Harry had lived as a child. Further

bombs fell on Wavertree Road on 7 October. This is probably the raid Aunt Mimi

would later recall as taking place the night John Lennon was born – there was

no actual raid on the ninth.

Wavertree

was now a clear target for the Nazis and the Harrison’s were not alone in

thinking each night could be their last. Wavertree Playground, known locally as

“The Mystery” and a favourite place for the locals to take their children was

bombed on the night of 4 November. Adjacent houses were damaged and a gas main

was fractured and caught fire only to be extinguished by a water main which

fortuitously burst nearby. The Germans had another go at the Edge Hill goods

depot on 12 November but missed. Stray oil incendiary bombs instead hit the

roof of the post office on Wavertree Road.

A map

showing the Edge Hill end of Wavertree - a major target for the Luftwaffe.

Several Beatles - related sites are visible including Bridge Road (former site

of Massey and Coggins), Cecil Street, Ash Grove (where both George's dad and my

own lived as children) and the LCPT social club where Harold Harrison arranged

a gig for the Quarry Men. Click to enlarge.

On the

evening of Thursday 28 November 1940 Rachael Lucas, known to all as ‘Nancy’ was

at home with her mother, Mabel Ashcroft, in Ashfield, a row of terraced housing

four streets away from Cecil Street, and five away from the Gas Works which

marked the end of Wavertree and the beginning of Edge Hill. Running down the

other side of the gas towers was Spofforth Road and it’s artery, Bridge Street

(where Paul McCartney would later work for Massey and Coggins) and beyond them

the huge railway sidings. Rachael worked as a post-girl delivering mail from

the Wavertree post office by bicycle. She’d once knocked a policeman over

during a blackout. On another occasion she was out during daylight with her

friend when a plane flew low over their heads. They both cheered and waved at

the pilot until somebody shouted ‘get down you bloody fools’, just as a second

plane came into view hot on the tail of the first. The second plane was an RAF

Spitfire or Hurricane. The first plane was German!

As soon

as the sirens sounded Rachael and her mother joined families all over Wavertree

and ran for the nearest cover, the communal air-raid shelter in the street or

the ‘Anderson’ shelter in the back garden, if they were lucky enough to have

one. Some preferred to hide under their own stairs, supposedly the strongest

point in the house. At the other end of Wavertree the Harrisons huddled with

their neighbours in the brick shelter built in the middle of Arnold Grove and

hoped for the best.

This

was a major attack by 324 aircraft. In the initial raid, Heinkel He 111s

dropped 30,960 incendiary bombs. As Thursday became Friday, Dornier DO 17 and

Junkers JU-88s dropped a mixed load over Wavertree comprising 356 tons of High

Explosives (including 151 ½ ton bombs), Flambo and 30 one- ton parachute sea

mines (of which 8 failed to explode).

This

was the night when the Junior Instruction Centre on Durning Road was hit by a

mine. The building collapsed and of the 300 people taking cover in the basement

shelter 164 were killed. Today it is remembered as the worst single loss of

life from bombing during 1940-41 in the UK.

The Gas

Works on Spofforth Road (above) and the Railway yard were prime targets for the

Luftwaffe but it was the houses within a square mile of the Wavertree Road area

that bore the brunt of the attack. By the end of the raid 2000 people were

homeless and the Gas Works were burning.

I

certainly remember the night the gas works went up. Imagine it was on Alfred

Street but I am not too good at remembering all the street names now. I lived

on Spekeland Vale, and remember the night and the next couple of days –

tremendous damage to the surrounding area of the gas works (Nita Jones,

Rootsweb)

The

street was Spofforth Road that took a pounding, it had the Co-op livery

stables, I think that the horses were untouched. We lived on Cambridge street

and took the blast which blew in the parlour window, the frame, the whole

works. I believe a navy bomb disposal man got awarded the highest possible

medal for his courage. Nights to remember, we spent a lot of time in the

community underground air raid shelter in Piggy Much Square. (Hugh Jones,

Rootsweb)

Sixteen

people lost their lives in Ashfield that night.

Rachael

and her mother survived the raid. Their home did not. The blast had blown the

front of the house out. Amazingly, standing in the street untouched amongst the

rubble was their upright piano. It didn’t have a mark on it.

Rachael

Lucas was my maternal Nan. When I was a child I’d ask her to tell me the story

about the piano that survived the bombing over and over again. She’d always

remind me “They were going for the gas works but missed and got us”.

A few

years ago I found this photograph of a piano in a bombed out street in

Liverpool. I couldn't believe it. Was this my Nan's piano? With further

research I established that the photo was taken in Bootle but the similarities

are plain to see.

Because

it was further away from the Gas works 12 Arnold Grove had fared better.

Emerging from the shelter the Harrisons were relieved to find their house was

still standing. It was not completely unscathed. The shockwaves from a huge sea

mine had blown all the windows in and the shards of glass had lacerated the

American leather sofa. Louise Harrison would later recall her mother joking ‘If

I’d known that was going to happen we could have been sitting on it all these

years!’

One of

the parachute sea-mines that miraculously failed to explode. Score Lane,

Childwall, about 1.5 miles from Arnold Grove.

The

last bombs to fall on Liverpool did so in January 1942 so I was surprised to

learn that the two oldest Harrison children were evacuated so late in the Blitz.

It seems that between 1942-43 Louise, then 10 and Harry,7 were sent to Wales,

staying with different families. Harry reportedly enjoyed his stay with a

family who had two teenage sons while his sister stayed with a childless

couple.

Around

May 1942 Louise found that she was pregnant again and this time it was planned.

With her oldest two children of a similar age it’s said that Louise wanted a

playmate for Peter.

Call

the midwife!

On

Thursday 25 February 1943 George Harrison was born in the front upstairs

bedroom of 12 Arnold Grove at ten minutes past midnight, entering a world he

later described as “deep in the Second World War, deep in Liverpool, and deep

in winter”. He was overdue and weighed a massive 10 ½ pounds with eyelashes,

long hair, full finger nails and brown hair.

In

those days Dads were not permitted in the room during the birth. The midwife

informed Harry he had a new son and he would later remember tiptoeing up the

stairs to meet him. He was shocked by what he found, “a miniature version of

me’’. He couldn’t believe how alike they looked.

The

next day Harry went to register the birth at Wavertree Town Hall without first

consulting Louise about a name for the new baby. Walking the short distance

along the High Street he decided on George and later reasoned if (the name) was

good enough for the King it should be good enough for him.

He was

baptised as Georgius Harrison on 14 March 1943 at Our Lady of Good Help. His

sister Louise and his aunt Mary (Fox, formerly French) were godmothers but for

some reason there was no godfather.

I had

two brothers and one sister. My sister was twelve when I was born; she'd just

taken her Eleven Plus. I don't really remember much of her from my childhood

because she left home when she was about seventeen. She went to teacher

training college and didn't come back after that.

My

grandmother - my mother's mother - used to live in Albert Grove, next to Arnold

Grove; so when I was small I could go out of our back door and around the back

entries (they called them 'jiggers' in Liverpool) to her house. I would be there

when my mother and father were at work.

Arnold

Grove was a bit like ‘Coronation Street’, though I don't remember any of the

neighbours now. It was behind the Lamb Hotel in Wavertree. There was a big

art-deco cinema there called the Abbey, and the Picton clock tower. Down a

little cobbled lane was the slaughterhouse, where they used to shoot horses.

My

earliest recollection is of sitting on a pot at the top of the stairs, having a

poop - shouting, 'Finished!' Another very early memory is as a baby, of a party

in the street. There were air-raid shelters and people were sitting around

tables and benches. I must have been no more than two. We used to have a

photograph of me there, so it's probably only because I could relive the scene

when I was younger, through the photograph, that I remember it.

VE Day

Party 8 May 1945 - from right Harry, Peter, Louise, and George aged 2. Note the

brick air-raid shelter behind Harry.

Our

house was very small. No garden. Two up and two down - step straight in off the

pavement, step right out of the back room.

Each

room downstairs was about ten feet square (very small) and yet despite the lack

of space the front room was never used. It had the posh lino and a three-piece

suite, was freezing cold and nobody ever went in it. We'd all be huddled

together in the kitchen, where the fire was, with the kettle on, and a little

iron cooking stove.

Like

many home of the time, there was no central heating, no bathroom and no indoor

toilet. The winters could be freezing. George later remembered that in the

winter there used to be ice on the windows and in fact you would have to put a

hot water bottle in the bed (keep nipping upstairs to keep it moving) then whip

your clothes off and leap in. And then oooooooooooohhh, lie still and then by

next morning you'd just got warm and then you'd wake up, "come on, time

for school", put your hand out of the bed. Freezing. Oh dear.

Harrison

recalled that he and his brothers dreaded getting up in the morning because it

was literally freezing cold and they had to use the outside toilet.

The

four children shared the back bedroom. In his infancy George had slept in his

parents room but he later moved in with his siblings, Louise in one bed, Harry

and Peter in another and George in a cot.

A later

resident of Arnold Grove was Anthony Hogan, author of From a Storm to a

Hurricane, the biography of Rory Storm and the Hurricanes. I asked him to

describe the layout of the house: The front door goes straight into the living

room which would have been about 12 foot square (I’m guessing here). At the

back was a small kitchen. The stairs are at the back of house. They go up from

the kitchen towards the front door if you get what I mean. Upstairs is a tiny

landing 2 foot x 2 foot. The front bedroom was the largest, and ran the length

of house across. The back bedroom runs towards back of house and is smaller.

(Anthony’s son) had a single bed, wardrobe, chest of drawers etc. There was not

much room with that in there, so imagine it with all those kids in there. The

houses were extended when we lived there. It was all knocked through so it had

space. Loved it there, the fans were funny at times. We needed a larger house.

Liked it there though.

A lot

of the garden was paved over (except one bit where there was a one-foot-wide

flowerbed), with a toilet at the back and, for a period of time, a little

hen-house where we kept cockerels.

Peter and George in the backyard at No. 12

There

was a zinc bathtub hanging on the backyard wall which we'd bring in and fill

with hot water from pans and boiling kettles. That would be how we had a bath.

We didn't have a bathroom: no Jacuzzis. Good place to wash your hair,

Liverpool. Nice soft water.

I had a

happy childhood, with lots of relatives around - relatives and absolutes. I was

always waking up in the night, coming out of the bedroom, looking down the

stairs and seeing lots of people having a party. It was probably only my

parents and an uncle or two (I had quite a few uncles with bald heads; they'd

say they got them by using them to knock pub doors open), but it always seemed

that they were partying without telling me.

I don't

remember too much about the music, I don't know whether they had (anyone

performing) music at the parties at all. There was probably a radio on.

There

was always music in the house, some of it quite unusual for the times. Louise

enjoyed listening to Indian classical music on ‘For the Indian Forces’ every

Sunday morning on BBC radio. It’s tempting to think her unborn fourth baby was

absorbing all this from the womb.

My

eldest brother, Harry, had a little portable record-player that played 45s and

33s. It could play a stack of ten records, though he only owned three. He kept

them neatly in their sleeves; one of them was by Glenn Miller. When he was out

everything was always left tidy; the wires, the lead and plugs were all wrapped

around, and nobody was supposed to use it. But as soon as he'd go out my brother

Pete and I would put them on.

We'd

play anything. My dad had bought a wind-up gramophone in New York when he was a

seaman and had brought it back on the ship. It was a wooden one, where you

opened the doors; the top doors had a speaker behind and the records were

stored in the bottom. And there were the needles in little tin boxes.

He'd

also brought some records from America, including one by Jimmie Rodgers, 'the

Singing Brakeman'. He was hank Williams's favourite singer and the first

country singer that I ever heard. He had a lot of tunes such as 'Waiting For A

Train', and 'Blue For A Train' and that led me to the guitar.

Harold

Harrison with his four children.

In the

late 1970s George took (his second wife) Olivia to see the house. No one was in

so they sat outside in the car and tried to imagine what it was like inside.

George suspected the new owners had at some point knocked the fireplace out,

installed “one of those little tiled jobs” and probably now had running hot

water.

I had

wondered whether George only went back the once. Did he ever take his son Dhani

to have a look? Did the new owner ever let him in?

Anthony

Hogan was able to confirm that George did make a return visit: Did you know

George once turned up at the house with his wife. (The lady living in number

12) Kath told us she answered a knock and he was standing there. He said he had

once lived there and asked if he could come in to look. He had a cuppa with

Kath.

(Somebody)

put a plaque up once without telling her. She came home and found it on her

house. She was so upset by it. I removed it for her. I should have kept it as

it would be worth a bit now.

Certainly

the current owners appear to want no part of the Beatles industry and this is

something one should bear in mind visiting any of the Beatles' former homes –

for the most part they are still occupied by ordinary people and their privacy

should be respected. I’ve stood at the corner of Admiral Grove and witnessed a

group of tourists peering through the window and leaning against the front door

of number 12 to pose for photographs. I think I’d get fed up with that every

day…..

George’s

brother Harry would later recall: Our little house was just two rooms up and

two rooms down, but, except for a short period when our father was away at sea,

we always knew the comfort and security of a very close-knit home life.

George

had similar fond memories of Arnold Grove:

It was OK that house, very pleasant being little and it was always sunny

in the summer. But then we moved, after about 25 years on the housing list, we

moved.

It was

actually nearer eighteen years since Harry and Louise had applied for a council

house. At the time of their original application they had one child, Louise,

who had since grown up and moved on. Now they had three more – Harry, fifteen,

Peter, nine and six years old George. On 1 January 1950 the Harrisons left

Wavertree and moved to a newly built home at 25 Upton Green in Speke.

Unfortunately they quickly wanted to move back. George: As soon as we got to

Speke we realised we had to get out of there, fast...the place was full of fear

and people smashing things up.

The

Harrisons got on another list.

Source:

The

George Harrison quotes are taken from his biography, ‘I Me Mine’ and interviews

given for ‘The Beatles Anthology’. The Books “Thats The Way God Planned It” by

Kevin Roach, and “Tune In” by Mark Lewisohn were also of assistance.

Thanks

to Anthony Hogan for his personal memories.