This is part two of my transcription of Thelma McGough’s interview

with Mark Lewisohn, which took place during International Beatle Week in

Liverpool last August.

Mark Lewisohn: So, these show a side (of John), obviously he’s gone through a lot of traumas, but he’s also still quite a human being, isn’t he? Able to connect with other people and find commonality there.

Thelma McGough: Well he wouldn’t do

it in public, but he’d do it in private.

[Continuing her story] And then he said: “Where do you live?” I said Knotty Ash, so then he started taking the piss again: “Ah! You’re one of the Diddy Men as well. Oh! You’re a pickled onion!” [1]

Anyway, he said what bus do you get? I said the no. 10, and he displayed this amazing knowledge of Liverpool bus routes [much laughter]. He said: “Why don’t you get on my bus, you can get off at Queens Drive, then get the 26 bus to Sheil Road by the Ice Rink, and then you can get the 10 from there”.

ML: Wow!

TM: And because I was poor I had a bus pass, so I thought its not going to cost me anything, so we went upstairs to the top of the bus and as we came towards Penny Lane he said can you come to ours later?

I said, I don’t know, he took my sketch book and did a little

sketch and drew Menlove, and drew a little cat, I think, and Mimi, and Me. He

said: “There you go, you get off at Vale Road”.

Of course, it’s three buses, it takes for ever. So, I did go back. [Laughs].

I was waiting on Queens Drive, the 72 bus that stopped outside his house only went every half hour, I missed it. So, some guy pulled up in a Jag, and offered me a lift, and I thought I’m not doing that. So, when I got off the bus he was still there (John, waiting) bless him, and I told him about the lift, and he said: “Oh people are posh round here, you should have taken it”.

I thought it’s all very well for you to say that, the News of the World is full of stories of girls getting murdered, y’know I’m not doing that.

And so that was the first time I went to Mendips.

On the corner of Vale Road, I haven’t been up there recently, there was this derelict cottage, like a farmhouse, and also there was an arch over the top of the road that went to the edge of the pavement, and there were lights and there were all these kids running round, you could hear them. And I asked (John) why they are still in school at this time of night, and he said it’s a home for naughty boys and girls; it’s called Strawberry Fields.

ML: Yeah, there was a remand home along there, just a few yards away. [2]

TM: I think that’s what it was, yeah. So that was the start of it all.

According to Thelma’s account, which she shared with Mark in 2010 for his book "Tune In," John would meet her at the bus stop. This stop was located near the corner of Vale Road, just before John’s house, and notably, it was very close to the site where Julia Lennon had tragically died the previous July.

Once they met, John and Thelma would cross Menlove Avenue and wait together in a nearby shelter situated on the edge of the golf course opposite Mendips. They would remain there until they were certain Mimi had left for her bridge game, and then cross back over. Thelma recalled that she only ever observed Mimi from a distance, and even then, only in the darkness.

ML: Right, how personal can we get in this conversation in front of an audience?

TM: Well,

you can ask and If I don’t want to answer I’ll tell you.

ML: How close did you and John get?

TM: As close as you can get

under the bed covers. Will that do?

[Cheers from the audience].

ML: That will do.

TM: Sorry. But that wasn’t allowed then, so…

ML: Yeah, and it was dangerous.

TM: I can say it now. I was seventeen, probably by the time I went to Mendips, nearly anyway, and I had no idea how you got pregnant.

ML: That’s why it was dangerous. But nothing happened thankfully, in that respect. Or maybe not thankfully, but anyway nothing happened.

TM: Well there was a point when I was in the girls cloakroom loo, and two of them were crying because they were going to have a baby, and I was in the cubicle, and I heard someone say – sorry about the language – “if you only do it a week after a period, and a week before, you won’t get pregnant”, and I thought: “Ah, I’ll remember that” (mimes writing in an imaginary notebook).

And then someone said, there’s a west Indian nurse in Canning Street where you can get an abortion for fifty quid, and I didn’t know what that was. Someone was talking and saying something happens with a knitting needle, and I though this is too much. But I remembered how not to get pregnant after that.

Which was awkward because John was very demanding about when he wanted to see you. And I didn’t want to tell him what the reason was, because it was too personal. But I’m telling you!

ML: Yeah, and all these people!

These were very different times and Liverpool was a very different place then, and general knowledge was a lot less limited than it is now, I mean now you can find out anything at any time, but in those days you were relying on hearsay, and little clues and information that you’d write down (mimics Thelma’s earlier mime).

TM: I have grand daughters who are talking sex at nine! And I’m broad minded but I think bloody hell how do they know all that?

ML: When I interviewed you for my book ‘Tune In’ you were very candid about why your relationship with John finished. It’s not something we really want to talk about it public but on the other hand, it would be naive to assume everything was always wonderful. So, he was going through a troubled spell, and you were on the receiving end. Is that fair?

TM: These days, I think even at school he’d be called ADHD. [3]

ML: ADHD? Yes, absolutely he would.

TM: He was full of fury and trauma, and so was I, and that’s how we bonded, and we had something in common, and sometimes, eventually it tips over… yeah.

ML: Frustration. Yes of course, it absolutely happens. I was talking to someone the other day about how everyone is labelled these days, children are labelled: ‘he’s got this, she’s got that’…

TM: Oh, he’d be labelled now.

ML: Yeah, I mean he went through all the classic circumstances of trauma there, but you just got on with it, there was no label attached, no special treatment…

TM: You couldn’t confide in anybody, and I’d never told anyone about my home background, except him, and you kept it in, and there’s something really primal, I think, about not having parents who support you, about people abandoning you, and you haven’t got that backup and it creates this… and also you feel as if you’re on your own.

ML: Yes, and that it’s your fault in some way, that you’re responsible for it.

TM: So, he was full of fury. So was I, and one time he…let loose and whacked me one.

And he did try and make up for it, but I wasn’t going to have it.

ML: That was the line

that he had crossed.

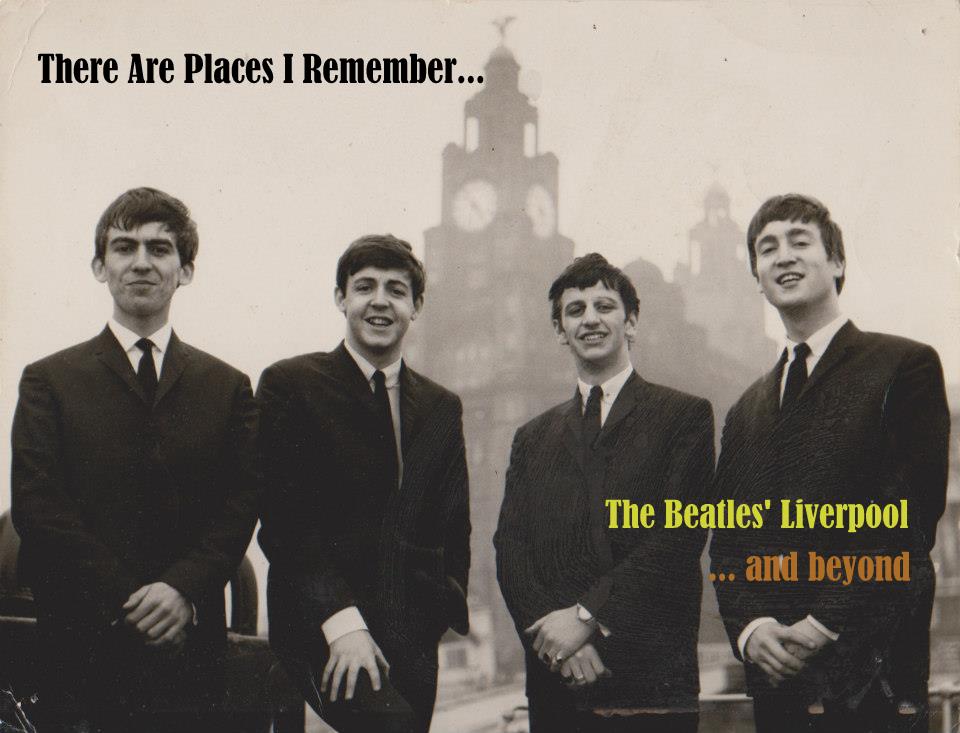

In part three we move the story forward to 1962 and hear Thelma talk

about her relationship with Paul McCartney and his family, and her first encounter

with local Beatlemania.

Notes:

[1] A reference to the much-loved Liverpool comedian Ken Dodd (above), who, like Thelma, lived in an area of Liverpool called Knotty Ash. Dodd made the area nationally famous and popularised the Diddy Men as a miniature race of people who lived there and worked in the local Jam Butty Mines. Many attribute this to Dodd's imagination, but they had already appeared in the earlier act of another Liverpool comedian, Arthur Askey. Askey was a former pupil at Liverpool institute. You'll never guess who owns Askey's old desk now.

Woolton Vale Remand Home for boys was situated at 239 Menlove Avenue. The house itself was originally built for Robert Gladstone (1834–1919), an East India merchant and the second cousin of British Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone. Following Robert Gladstone's death, his former home became known as the 'Woolton Country School for Boys', operating as a remand home. This institution could accommodate up to 36 boys, many from inner-city backgrounds, some as young as seven years old. The boys were sent there for a variety of misdemeanours, including theft, anti-social behaviour, and truancy.

John Lennon later recounted that there were two notable

houses near his childhood home: "One was owned by Gladstone: a reformatory

for boys, which I could see out my window, and Strawberry Field, just around

the corner from that, an old Victorian house converted for Salvation Army

orphans".

I think Thelma has conflated her memories here. The

pedestrian tunnel they walked through was excavated below Gladstone’s former

billiard room, so the children she could hear were playing above her (or in the

adjacent gardens). Strawberry Field(s)

was higher up Beaconsfield Road, behind Woolton Vale, and probably out of

earshot, though at one point prior to John’s time in Woolton the gardens had

extended as far as Menlove Avenue.

Given the proximity of these institutions, it is not

difficult to imagine that John Lennon—himself the product of a broken home and

taken into care by his aunt and uncle because his parents were unable or

unwilling to care for him—might have felt a natural affinity with the rejected,

unloved, and emotionally damaged children he encountered.

In one of his final interviews, Lennon admitted that his

influences ranged from Lewis Carroll and Oscar Wilde “to tough little kids that

used to live near me who ended up in prison and things like that”. In this

light, it might be argued that the song 'Strawberry Fields Forever' drew as much

inspiration from Woolton Vale as it did from the Salvation Army home.

Liverpool Remand Home as it became known closed in disgrace

in the late 1970s after allegations were made about staff ill treatment of the

children. The building was eventually demolished around 1990. While I have no

clear memory of the structure itself, evidence of where it once stood can still

be found by walking along the section of Menlove Avenue between Beaconsfield

and Vale Roads.

[3] Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

No comments:

Post a Comment